Osteoarthritis Depression Impacts and Possible Solutions Among Older Adults: Year 2021-2022 in Review

Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis, a serious joint disease, said to represent a generally declining state of wellbeing and function among many older adults has been shown to be affected to a considerable degree by various negative beliefs and inactions rather than degradation alone.

Aim

This review examines the case of depression as this pertains to the older adult with osteoarthritis of one or more joints. Specifically, the most up to date information on this topic was sought, as care improvements over the past decade have not shown any impactful population wide results.

Method

Reviewed were relevant 2021-2022 research and review articles specifically pertaining to what is being observed currently by researchers as far as osteoarthritis-depression linkages goes, as these may reveal opportunities for more profound research, and practice-based endeavors.

Results

In line with 60 years of prior research, it appears a clinically important role for depression in some osteoarthritis cases cannot be ruled out. It further appears that if detected and addressed early on, many older adults suffering from osteoarthritis may yet be enabled to lead a quality life, rather than a distressing and excessively impaired state of being. Those older osteoarthritis cases requiring surgery who suffer from concomitant depressive symptoms are likely to be disadvantaged in the absence of efforts to treat and identify this psychosocial disease correlate.

Conclusion

Providers and researchers are encouraged to pursue this line of inquiry and begin to map clinical osteoarthritis measures with those that can track cognitive patterns, musculoskeletal, features and inflammatory reactions along with valid depression indicators among carefully selected osteoarthritis sub groups.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2022 Ray Marks

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Background

It is well established that among the many health challenges that appear to inflict older adults more readily than younger adults, those who develop or suffer from painful disabling osteoarthritis of one or more joints may react by acquiring various symptoms of depression, an important correlate of disability in older adults in its own right, in addition to all the challenging symptoms of this painful commonly progressive biomechanical joint disease 1. However, even though the onset and trajectory of depression in this instance can possibly be averted in efforts to prevent excess functional disability and hardship, until recently, the overall evidence base that prevails on the topic of osteoarthritis has shown very little evidence of any concerted effort to either study or intervene upon this potentially highly relevant disease correlate.

At the same time, even less evidence of a need to examine potential remedies in this regard appears to prevail. Indeed, even as recently as 2021, a review of the literature in that year truly failed to mention the distinct category of depression, even though multiple other osteoarthritis research and clinical topics were highlighted 2. In 2022, as conducted June 9, a yearly review on PUBMED showed the use of the term ‘osteoarthritis’ yielded 8433 posted articles and only 167 were categorized as being associated in some way with the presence of or impact of depression, when compared to the role of medications with 3800 citations and 496 articles referring to pain.

In addition, even though rates of osteoarthritis topical studies involving depression have increased since 2015, as with those published in the past, several current citations when scanned clearly fail to examine the relationship between depression and its collective impact on the older adult diagnosed as having osteoarthritis to any high degree. In addition, cohorts in some studies could not be readily classified as being older adults (65 years >) (eg., 3) or as well defined cases of either early or moderate osteoarthritis of any joint except the knee. Others examined samples of osteoarthritis cases alongside cases of inflammatory arthritis or other comorbid conditions associated with depression, or rendered conclusions based on pre-collected historical data 4, where deductions were made retrospectively or based on regression models of baseline data rather than actual observations 5. Moreover, the joints studied and their diverse degrees of pathology within and across studies plus discrepant inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with differential modes of assessing osteoarthritis severity, as well as depressive symptom duration and severity, generally precluded any meaningful synthesis.

As a result of a possible belief osteoarthritis is not a psychosocial disease, among other factors, for example, lack of funding support, what remains is a reasonably sparse fragmented data base if we consider all the other themes explored systematically and comprehensively over the same time period. What still remains unclear is how many older adults do actually suffer from a depressed mood due to osteoarthritis, plus the actual relationships and importance of addressing depression in the specific context of varying osteoarthritis symptoms and disease stages and joints, rather than pursuing a more standard and total reliance on a uni-dimensional biomechanical disease perspective that has clearly not borne sufficient ‘fruit’. Additionally, even when assessed empirically, depression oriented survey instruments differ, as do their cut-off points, and mechanisms of summation and interpretation. Hence what is needed, and what might be done to avert or minimize the emergence of depressive symptoms in tandem with other osteoarthritis intervention approaches remains largely speculative at best.

Given that osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis, is largely irreversible and that older people are more likely than younger persons to suffer from this condition, and the more severe the disease, and more rapid its progression, the greater the likelihood of acquiring reactive depression 5, the goal of this report was to examine the strength and quality of the current evidence base concerning any linkages between depressive symptoms and osteoarthritis pathology that warrant more careful attention, especially that which has emerged in the past year, and to reflect on some past work in this area in order to arrive at some appropriate recommendations for advancing clinical practice in this area. The unrelenting personal and societal burden imposed by osteoarthritis among the older population, the multiple negative impacts on adults with osteoarthritis as a result of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, and the ill-effects of excess body weight, and narcotic and other medications on overall wellbeing in this condition that persist can be hypothesized to render the role of depression in the osteoarthritis disease cycle more important than ever in the older adult population 6. As such, this review elected to focus specifically on examining the current data in this regard and whether a need exists for more research and clinical efforts to address, avert, or ameliorate any prevailing symptoms of depression in the context of osteoarthritis care. To this end, this review describes:

Some selected findings concerning osteoarthritis and depression.

The implications of the current research for improving practice.

It was felt this information would be consistent with the need for continuing efforts to broaden our knowledge base concerning factors that impact osteoarthritis disability, particularly as this occurs among older adults. The information was also deemed consistent with the goal of identifying what prevention/intervention strategies other than those currently considered standard practices might prove efficacious in the future for maximizing the affected individuals’ functional status and overall life quality, while minimizing the extent of the anticipated disease progression. Commonly a neglected area of therapeutic concern, and often not even mentioned in the context of clinical practice recommendations, the author’s purpose was to provide a firm rationale for supporting continuing efforts in this regard.

Accordingly, in the first section of this work, some current findings concerning the topic of osteoarthritis and depression and its observed linkage and implications are presented. The work concludes by summarizing the key findings from these data and by providing related guidelines for clinical practice and future research endeavors.

Methods

The desired information was compiled from an extensive review of the English language literature embedded in the PUBMED over the past year, as well as selected articles published since 1980. The goal was to provide a comprehensive overview of this topic that might be noteworthy in efforts to foster healthy aging. Using the keywords: Osteoarthritis and Depression, alone or in combination the following were located as of June 9, 2022

Additional relevant materials published in the English language as full length articles and covering the years 2000-2020 were also scanned, as were bibliographic resources if they pertained to the present topic.

The search, conducted by the author, was limited however, by excluding studies detailing the link between depression and many other health issues such as rheumatoid arthritis, conference abstracts, preprints, studies on depression in the context of prosthetic implant surgery, adolescent based studies, intervention studies, and those that did not directly address the current topic. All forms of report were deemed acceptable though if they appeared to address one or more items of present interest, and only a narrative overview of what has emerged to date is provided. Even though the current review does not discuss or analyze the nature of the varied experimental and review report approaches studied in detail, nor the metabolic and pain pathways and others associated with osteoarthritis and depression, this current review chose to accept the face value of the various experiments and reports that constitute the prevailing body of peer reviewed research posted in the world’s most comprehensive database as of June 2022, as well as their conclusions.

Emphasis was placed on examining current articles published between June 2021-2022 so as to establish the state of the art in this regard, given that improvements in osteoarthritis care may have emerged recently and impacted the findings that predate this period. These data were then compared to and discussed in light of former research in this area.

Results

Over time, a cursory overview of PUBMED, the world’s leading and most comprehensive medical repository shows the combined topic of osteoarthritis and depression emerged as a theme on its data base in 1954 and since then has slowly been increasing to reach 1967 items as of June 2022. Of these are 202 clinical trials, 171 randomized trials, and 34 meta analyses of which only one directly addresses depression and was published in 2016.

Yet, even though the rate of publications has increased quite substantively in the past two years in particular, many gaps remain with few well-informed empirically validated intervention solutions and almost no uniform study design, and assessment procedures. Nonetheless, among the 167 currently listed studies as of June 9, 2022, one noteworthy study is that by Parmelee et al. 7 who sought to examine the main and moderating effects of global depressive symptoms upon in-the-moment associations of pain and affect among individuals with knee osteoarthritis (N=325) who completed a baseline interview tapping global depressive symptoms showed the construct of global depression as measured in the study predicted current pain, as well as both positive and negative emotional affect, in addition to changes in pain and affect over a 3-8 hour period. This observed association between the measures made of pain and negative affect was stronger in those cases who documented higher rates of depressive symptoms as far as both momentary pain experiences, as well as those occurring over short time periods. While no moderating effect for any positive affect-pain association was found, the presence of depressive symptoms, which correlated with pain variability as well as negative affect, led the authors to conclude that previous work on the relationship of chronic pain and global depressive symptoms are valid for explaining short term and momentary osteoarthritis pain experiences. How many subjects had clinically verifiable depression, the accuracy of the pain estimates, and how severe or protracted this was, was not clearly established, however.

As identified though in an article designed to examine correlations between pain severity and levels of anxiety and depression in adults with osteoarthritis patients, Fonseca-Rodrigues et al. 8 using four databases from inception up to 14 January 2020 including 12 original articles and 121 studies, with a total of 38 085 participants, mean age 64.3 years old showed a moderate positive correlation between pain severity and depressive symptoms that cannot be readily overlooked. In addition, Schepman et al. 9 who employed a nationally representative survey to generate data concluded that cases reporting moderate to severe pain on a daily basis often exhibited signs of depression, while Furlough et al. 10 found a correlation between osteoarthritis disease duration and depression symptoms in cases with either hip or knee osteoarthritis. Barowsky et al. 11 show that osteoarthritis and major depression appear to share common genetic risk mechanisms, one of which centers on the neural response to the sensation of mechanical stimulus that should be explored further. As well, this research points to the strong impact of depression on the health status and general condition of the adult with osteoarthritis, that occurs more often in the case where the adult feels helpless and unconfident 12, and may induce a deleterious impact on management in general, as well as on surgery outcomes where this is needed 3, 13.

In fact several papers stress a highly negative role for pre surgical depression as this impacts the extent of recovery post joint replacement surgery significantly and predictably 14, even if the affected adult is not considered at all ‘old’ 12. As well, those suffering from a long standing or chronic major depressive disorder 11 may encounter an unrelenting cycle of pain and disability rather than any simple unidirectional cause effect association 15. Other research shows that delaying the opportunity to intervene on the presence of depression regardless of cause or type is likely to do more harm than good in as many as 50 percent or more of osteoarthritis cases 16, especially where perceptions of any cumulative or perceived discrimination prevail 2, 5. Those cases who present with comorbid insomnia 12 or a newly diagnosed joint lesion may be especially vulnerable 17.

Wang and Ni 18 concluded that depression, one of the most common comorbidities in people with osteoarthritis is important because it clearly affects patient prognosis and quality of life, plus the overall disease burden. Moreover, it is a key contributor to pain, poorer health status and life quality, productivity and activity impairments. In addition, the presence of depression, often linked to pain, and more evident in the face of severe pain 19, 20 may increase the risk for restless sleep among cases with osteoarthritis of the knee 21, and according to Furlough et al. 10 many reports state that osteoarthritis, the most common joint disease, often produces lengthy periods of chronically intractable joint stiffness and swelling, as well as multiple functional, social, occupational, and emotional challenges and restrictions, as well as feelings of depression that flow from this 19, 20. Depressive presence may also impact surgical outcomes negatively 6, as well as sleep disturbances, overweight or obesity, pain, plus the presence of comorbid health conditions 22, hence surgeons and others have been increasingly encouraged not to neglect to screen for any undue depressive manifestations in their osteoarthritis clients 23, especially in light of the possible associations between a subject’s psychological profile and their somatosensory function and brain structure 30.

As noted by Jeong et al. 24 adults with arthritis who become worse or stay the same over time are more likely than not to develop depressive symptoms than those who are disease free, regardless of cohort studied, or younger age 25. Therefore, even if not associated with pain exacerbations 26, timely mental health evaluations and appropriate management interventions are highly recommended for those patients with arthritis who do not improve or who undergo changes in their disease status, as well as those who desire their clients to experience a high rather than a low life quality 27. More specifically, as per Rathburn et al. 28 depression interventions if required or indicated could be optimized by targeting the specific symptomology that these subtypes exhibit.

As well, efforts that focus on this high risk group as far as increasing functional exercise, positive social interactions and support, and lower limb muscle strength training could help towards addressing both depression 29 along with other physical health and mental health risks 30 even if quite recent data fail to include depression among the personal modifiable risk factors for osteoarthritis disability or any osteoarthritis phenotype eg.31, 32, even though this common psychological attribute of suffering cannot be discounted. The role of the provider in this regard, which appears of key import 18 is also not widely highlighted. In addition, the fact that one or more forms of long standing clinical depression can induce several chronic health conditions that might predispose to joint derangement, as well as detrimental post operative outcomes has been poorly studied. Regardless of depression category and its origin, a wealth of research predicts unrelieved feeling of depression, may not only be expected to foster negative health and life quality outcomes, but may be especially harmful if this engenders a predictable increase in central nervous system sensitivity to incoming neural stimuli among cases with intractable osteoarthritis that is found to have the potential to greatly amplify the pain experience of the depressed individual 33, 34, even if the actual extent of joint pathology itself is not striking. Similarly, even if receiving prompt medical care, a negative set of provider beliefs concerning osteoarthritis, can be expected to heighten the risk of acquiring persistent and incremental feelings of depression or helplessness as well as negative patient beliefs that are not commensurate with the prevailing degree of osteoarthritis joint damage, but which the sufferer feels unable to deal with or alleviate. At the same time, even if only moderate, the prevailing state of joint pathology can be expected to worsen over time, along with an increase in adverse reactions to any persistent impairments and possible spread of the disease to other joints, along with a low life quality, and an increased need for more radical rather than conservative intervention approaches 36 and worse than anticipated outcomes of function 37.

As a result, there can be no question as to whether averting rather than unravelling this cycle of deleterious interactive health events and examining what specific interventions may be most beneficial to the individual patient with this condition is likely to be strongly warranted in most older adults suffering from advanced osteoarthritis. Unfortunately, even though more than 80 percent of this older osteoarthritis population may be in constant pain and have difficulty in accomplishing everyday tasks, current treatment approaches often fail to mitigate this, as evidenced by persistent high rates of joint replacement surgery and evidence of substantive pre surgical depressive symptoms 37, and in many cases associated feelings of sadness, loss of interest and pleasure in daily activities 36 even when surgery is successfully enacted.

Fortunately, depression can be reasonably well diagnosed by taking a careful history, and by applying one or more validated scales to examine if indeed the individual is depressed, and if so, how severe the condition is. It can be treated to some effect by efforts to minimize stress, chronic unrelenting pain and inflammation by employing counselling, psychotherapy, medications, cognitive behavioural therapy, exercise, and social support among other approaches. Treating any prevailing comorbid conditions, while enhancing coping skills may also be beneficial.

Indeed, the proactive willingness and desire of the primary caregiver to take the time to examine the personal situations facing their older clients who may be experiencing or exhibiting depressive symptoms, and intervening thoughtfully and empathetically upon discovering any presiding or probable risk of incurring these symptoms, may be expected to not only assist in alleviating immense degrees of suffering due to pain in this sub group, but impairments due to excess stiffness, low levels of vitality, excess fatigue and lack of motivation. Moreover, research strongly supports the likelihood of better patient outcomes if patients feel more optimistic than not, and believe they can care for themselves successfully, and discussions about any unrealistic expectations and the importance of maximizing mental health and avoiding distress are forthcoming 38, 39.

Discussion

In the struggle for practitioners and patients to achieve successful osteoarthritis outcomes, as outlined above, psychological attributes such as feelings of depression are undoubtedly a highly salient explanatory factor of excess osteoarthritis disease manifestations and severity and a lower than desirable life quality 39. In this regard, prior and current literature describing the prevalence and impact of co-occurring depressive symptoms among older adults with osteoarthritis, supports a role for the idea of preventing or treating the presence of depression in a population even though the key pathological explanation for osteoarthritis is commonly accepted as a physical one. As such, it appears that ignoring the presence of any co occurring mood disorder or reactive depression can no longer be considered a dispensable consideration in efforts to ameliorate or avert severe disabling osteoarthritis among a fair percentage of the older population. As shown by Taveres et al. 40 who advocated treating multiple neural targets especially in the case of the older adult suffering from osteoarthritis with intractable pain, this approach is likely to help improve rather than hinder the affected adult’s sleep and activity practices, morale, anxiety, and self efficacy for coping with their osteoarthritis disability, while raising their self-worth. Moreover, since the patient’s negative perceptions and reactions to their impairment may reinforce pain, efforts to mitigate persistent feelings of distress also predict fewer coping challenges, inflammatory responses, excess medication needs, excess eating or appetite losses, plus increased chances of acquiring or exacerbating an array of co existing physical illnesses, memory challenges, weakness, social implications and an excess need for existing health services.

Unfortunately, although a scan of the currently available data show the presence of unwanted depressive symptoms appears to be present quite commonly in many older adults diagnosed as having osteoarthritis especially among those cases requiring total joint replacement surgery, showing the degree of depression is substantial in many cases, very few articles to date have tested the idea of preventing this state, which tends to persist in many post surgical cases. Moreover, little attention appears to be directed to the fact older adults may already be suffering from long standing trait based depression, rather than reactive depression, or both, and multiple co existing illnesses associated with depression. At the same time, even if treatable, unless sought by the provider, emotional attributes such as depression may be overlooked due to false beliefs stemming from the mythology that nothing can be done for osteoarthritis, that osteoarthritis is a biomechanical disease, not a psychosocial disease, or that mental health issues are highly stigmatized in society, thus not put forth by the patient proactively, and are thus not reported. Yet, current data reveal that the caregiver should be suspicious in this regard especially if their clients seek help more often than anticipated, and describe an increase in sleep disturbances, activity avoidance practices, a low sense of morale, anxiety, and diminished self efficacy for coping with their disability, plus a low self-worth and persistent feelings of distress, and fatigue. Those who exhibit excessive inflammatory responses, excess medication needs, excess eating or appetite losses should also be more carefully evaluated in efforts to reduce reliance on harmful medications and existing health services, while aiming to foster a high rather than a low life quality plus a strong degree of satisfaction 40. As well, and in the context of osteoarthritis, a disease frequently associated with obesity and cardiovascular problems including diabetes 41, those with functional impairments and depression 42 may exhibit high levels of non-compliant behaviors, activity avoidance, catastrophizing, and passive coping styles 43, plus higher levels of psychopathology than non-distressed controls 44, 45, especially in cases with marked joint destruction and poor walking ability 46.

These potentially modifiable disease associated factors not only predict future depression and/or pain onset or worsening 47, 48, but adverse or delayed outcomes following either hip or knee total joint replacement surgery 40. Moreover, they may explain why those with generalized osteoarthritis suffer more losses in leisure time activity performance than controls 49, and why they exhibit greater rates of disease-associated consequences with relatively lower health than those with knee or hip problems alone 50, along with greater disability, a reduced ability to cope, further depression, and more pain (p<.05) 51, 52.

At the same time, those experiencing psychological distress may be less motivated towards self-care, as well as less optimistic about engaging in treatments deemed crucial for minimizing their disability such as exercise 53, 54, and may yet have a lower life quality, higher pain and body mass scores plus more stiffness than desirable in spite of receiving a surgical joint replacement to counter this 13, 54.

In any event, current research as well as multiple observations carried out over the past 40 years among a fairly representative sample of osteoarthritis cases have specifically shown a relationship to exist between depression and osteoarthritis, including less effective cognitive coping strategies 55 that would strongly support the possible added value of improved routine efforts to identify, study, and treat this psychosocial factor.

Moreover, it seems safe to say older adults with osteoarthritis and concomitant depression who remain untreated are more likely to require high doses of pain relieving medications, as well as more health services than those with no depression 56. They may also have fewer social contacts, a poor life quality, and excessively high body mass indices compared to those osteoarthritis cases not experiencing depression 57, 58.

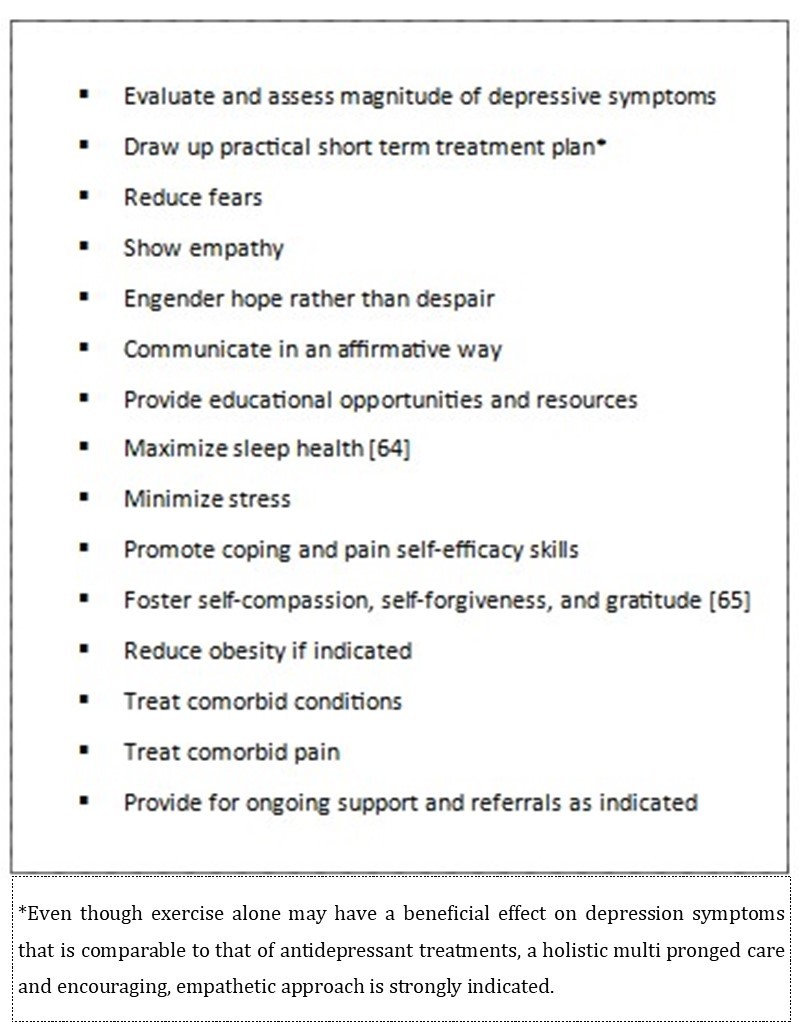

To this end, efforts to impact depression directly, including some form of cognitive behavioral therapy, emotional and social support, plus a combination of adequate nutrition, exercise, stress control strategies, weight management, and sleep, plus efforts to minimize inflammation and negative beliefs would all appear promising (Box 1). Minimizing the extent of any comorbid condition, such as cardiovascular disease, insofar as these conditions can heighten the risk for excess feelings of depression can potentially help affected individual’s to experience less pain, and suffering. Finally, reducing the stigma of depression may be helpful as well, as may addressing any prevailing perceptions of disadvantage rather than omitting to do this. Importantly, even though poorly studied, or discussed during training of medical providers, it is clear thoughtful patient oriented provider approaches are strongly indicated 1.

Box 1.Selected Strategies for Preventing and Treating Osteoarthritis and Depression and Enhancing Mental and Physical Outcomes and Comfort

It is also argued that because stress and depression are both associated with the development of later life medical co-morbidities, as well as the possible onset and worsening of osteoarthritis pain, disability, and poor health, plus possible excess opioid usage 66, very careful evaluation to tease out the presence of physical symptoms, versus emotional distress, followed by interventions such as relaxation, is strongly indicated 67, and may be especially helpful in reducing osteoarthritis related disability, among those who are over-anxious and/or chronically ill. In turn, therapies that foster feelings of efficacy and confidence and engage the mental and social capacities of the arthritis sufferer are expected to positively impact overall well-being, including walking ability as well as mental health status 68, 69, 70, 71. Educational approaches that can foster both a more positive outlook, as well as an individual's self-management capacity, may similarly heighten the life quality of the individual osteoarthritic patient who feels sad and distressed, especially those older adults with little social support or negative views, those with a family history of psychiatric problems, those with long standing medical conditions, those experiencing prolonged stress, and those with limited resources.

As per Sanftennerg et al. 58, in light of the finding that most forms of depression can clearly decrease health-related quality of life, while compounding the severe disability experienced by many older adults suffering from osteoarthritis, the presence or tendency towards any co occurring depression should not be disregarded or overlooked in the context of health care delivery for this patient group that seeks to maximize this, as well as health care utilization and costs. In this regard, the application of multi-pronged interventions that specifically target both pain-related physical as well as psychological risk factors that can accompany other medical challenges commonly faced by people with osteoarthritis, such as obesity, sleep apnoea, pain in other joints 59 pain sensitivity 73, lower levels of brain derived pain mediators than healthy adults 74, appear strongly indicated, and can possibly help allay, rather than heighten fears about undertaking recommended activities or rehabilitation directives, as well as any provider related confusion 60. This approach may also encourage a more active, rather than a sedentary lifestyle 61, while mitigating non-specific somatic symptoms other than pain, such as fatigue, and sleeplessness that tend to compound the extent of any existing health complaints as well as the overall disease prognosis 62, as well as narcotic usage 75, even if this only minimally measurable 63, 70 and needs to be further explored in the future.

Concluding Remarks

This current overview of an increasingly important health topic clearly shows that despite more than a century of research, osteoarthritis remains a highly prevalent oftentimes progressive chronically disabling health condition affecting one or more joints of the older adult and that engenders great suffering that demands more carefully developed efforts to counter excess joint destruction.

Although long considered a disease that largely impacts physical functioning quite markedly, even after surgery, the presence of co-occurring depression histories or reactive symptoms of depression that are continuing to be observed at oftentimes high rates among osteoarthritis cases requiring surgery, as well as many who may be in the early disease stages, strongly suggests that this health variable has been neglected as salient in many cases to date despite a relative wealth of research implicating depression in the osteoarthritis pain and disability cycle.

At the same time, and with no current universally available means of a cure, and a population that is generally older than that studied to date, and who may be unable to utilize pharmacologic interventions safely, it appears the role of all possible reversible correlates of this disease, such as depression should not be overlooked.

In particular, efforts to address the multiple sources of osteoarthritis pain, plus efforts directed towards preventing or stabilizing other related health issues, including excess weight gain, may be especially helpful. Addressing depression and its manifestations directly where present may be expected to further help to improve the patient’s overall health status, while reducing the need for dangerous narcotics. Fostering the ability of the older adult to understand the role of negative emotions on overall wellbeing and to be an active player in their recovery or maintenance may not only reduce excess depressive feelings, but enhance motivation for recovery that lead to optimal health outcomes.

By contrast, it can be concluded that after more than 60 years of study focusing on emotional factors, which is gaining and has gained considerable momentum and validity, a persistent focus purely on the physical attributes of osteoarthritis and exclusion of emotional factors as salient can be expected to yield a less than optimal health outcome, life quality, and progressively waning degree of independence for the afflicted older adult, particularly among those with new diagnoses, those who have longstanding disease histories, plus those cases with severe or chronic pain, and multiple joint problems, as well as those who are indigent, overweight, those who report high levels of stress and fatigue, and have few social contacts.

As such, and even before more confirmatory research in forthcoming in this realm, we would argue that sufficient collective and emerging data and clinical research observations strongly indicate that among the most potent keys to success in regard, may lie in the provider’s appreciation that osteoarthritis involves wide variations in disease manifestation, and many dimensions, including an emotional dimension. We further conclude that their concerted efforts to harness their collaborative and empathetic communication skills including a willingness to routinely assess osteoarthritis sufferers for any associated depressive symptoms or risk thereof, and to include incremental ‘corrections’ of disease misperceptions and modifications of any prevailing self-management regimen will reap immense achievable cost-saving and life affirming benefits.

Equally important is the mindset of the patient and significant positive results can be anticipated here by the caregiver who engenders an encouraging rather than a negative foreboding disease perspective in light of the profound link between osteoarthritis disability and emotional health confirmed in current research at all disease stages.

References

- 1.Lentz T A, George S Z, Manickas-Hill O, Malay M R, O'Donnell J et al. (2020) What general and pain-associated psychological distress phenotypes exist among patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 478(12), 2768-2783.

- 2.Quicke J G, Conaghan P G, Corp N, Peat G. (2022) Osteoarthritis year in review. 2021: Epidemiology & therapy. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 30(2), 196-206.

- 3.Costa D, Cruz E B, Silva C, Canhão H, Branco J et al. (2021) Factors associated with clinical and radiographic severity in people with osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional population-based study. Front Med (Lausanne). 8, 773417.

- 4.Jiao J, Tang H, Zhang S, Qu X, Yue B. (2021) The relationship between mental health/physical activity and pain/dysfunction in working-age patients with knee osteoarthritis being considered for total knee arthroplasty: A retrospective study. , Arthroplasty 3(1), 22.

- 5.Li M, Nie Y, Zeng Y, Wu Y, Liu Y et al. (2022) The trajectories of depression symptoms and comorbidity in knee osteoarthritis subjects. , Clin Rheumatol 41(1), 235-243.

- 6.Song J, Lee J, Lee Y C, Song J, Lee J et al. (2021) Sleep disturbance trajectories in osteoarthritis. , JCR: J Clin Rheumatol 27(8), 440-445.

- 7.Losina E, Song S, Bensen G P, Katz J N. (2021) Opioid use among Medicare beneficiaries with knee osteoarthritis: prevalence and correlates of chronic use. Arthritis Care Res. , (Hoboken)

- 8.Parmelee P A, Behrens E A, Costlow Hill K, Cox B S, DeCaro J A et al. (2021) Momentary associations of osteoarthritis pain and affect: depression as moderator. , J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. B. Dec 5.

- 9.Fonseca-Rodrigues D, Rodrigues A, Martins T, Pinto J, Amorim D et al. (2021) Correlation between pain severity and levels of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 61(1), 53-75.

- 10.Schepman P, Thakkar S, Robinson R, Malhotra D, Emir B et al. (2021) Moderate to severe osteoarthritis pain and its impact on patients in the United States: A national survey. , J Pain Res 14, 2313-2326.

- 11.Furlough K, Miner H, Crijns T J, Jayakumar P, Ring D et al. (2021) What factors are associated with perceived disease onset in patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis?. , J Orthop 26, 88-93.

- 12.Barowsky S, Jung J Y, Nesbit N, Silberstein M, Fava M et al. (2021) Cross-disorder genomics data analysis elucidates a shared genetic basis between major depression and osteoarthritis pain. , Front Genet 12, 687687.

- 13.A Van Dyne, Moy J, Wash K, Thompson L, Skow T et al. (2022) Health, psychological and demographic predictors of depression in people with fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis. , Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(6), 3413.

- 14.Mahdi A, Hälleberg-Nyman M, Wretenberg P. (2021) Reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms one year after knee replacement: a register-based cohort study of 403 patients. , Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 31(6), 1215-1224.

- 15.Aggarwal A, Naylor J M, Adie S, Liu V K, Harris I A. (2022) Preoperative factors and patient-reported outcomes after total hip arthroplasty: Multivariable prediction modeling. , J Arthroplasty 37(4), 714-720.

- 16.Lu H, Wang L, Zhou W, Chen H. (2022) Bidirectional association between knee osteoarthritis and depressive symptoms: evidence from a nationwide population-based cohort. , BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23(1), 213.

- 17.Kwiatkowska B, Kłak A, Raciborski F, Maślińska M. (2019) The prevalence of depression and insomnia symptoms among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis in Poland: A case control study. , Psychol Health Med 24(3), 333-343.

- 18.Dell'Isola A, Pihl K, Turkiewicz A, Hughes V, Zhang W et al. (2021) Risk of comorbidities following physician-diagnosed knee or hip osteoarthritis: a register-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. , (Hoboken)

- 19.Wang S T, Ni G X. (2022) Depression in osteoarthritis: Current understanding. , Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 18, 375-389.

- 20.Jin W, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Che Z, Gao M. (2021) The effect of individual musculoskeletal conditions on depression: updated insights from an Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging. Front Med (Lausanne). 8, 697649.

- 21.Burant C J, Graham G C, Deimling G, Kresevic D, Kahana E et al. (2022) The Effects of osteoarthritis on depressive symptomatology among older U.S. military veterans Int J Aging Hum Dev. 914150221084952.

- 22.Mulrooney E, Neogi T, Dagfinrud H, Hammer H B, Pettersen P S et al. (2020) Sociodemographics, comorbidities and psychological factors and their associations with pain & pain sensitization in hand osteoarthritis. , Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 28, 424-425.

- 23.Beaupre L A, Kang S H, Jhangri G S, Boettcher T, Jones C A. (2021) Impact of depressive symptomology on pain and function during recovery after total joint arthroplasty. , South Med J 114(8), 450-457.

- 24.Bian T, Shao H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Song Y. (2021) Does psychological distress influence postoperative satisfaction and outcomes in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? A prospective cohort study. , BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1), 647.

- 25.Jeong S H, Kim S H, Park M, Kwon J, Lee H J et al. (2021) Arthritis status changes and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Koreans: Analysis of data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging survey. , J Psychosom Res 151, 110662.

- 26.Aqueel M, Rehma T, Sarfraz R. (2021) The association among perception of osteoarthritis with adverse pain anxiety, symptoms of depression, positive and negative affects in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. , J Pak Med Assoc 71(2), 645-650.

- 27.Fu K, Metcalf B, Bennell K L, Zhang Y, Deveza L A et al. (2021) The association between psychological factors and pain exacerbations in hip osteoarthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 60(3), 1291-1299.

- 28.Park Y, Park S, Lee M Y. (2021) The relationship between pain and quality of life among adults with knee osteoarthritis: The mediating effects of lower extremity functional status and depression. Orthop Nurs. 40(2), 73-80.

- 29.Rathbun A M, Shardell M D, Ryan A S, Yau M S, Gallo J J et al. (2020) Association between disease progression and depression onset in persons with radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 59(11), 3390-3399.

- 30.Zheng X, Wang Y, Jin X, Huang H, Chen H et al. (2022) Factors influencing depression in community-dwelling elderly patients with osteoarthritis of the knee in China: A cross-sectional study. , BMC Geriatr 22(1), 453.

- 31.Johnson A J, Laffitte Nodarse C, Peraza J A, Peraza J A, Valdes-Hernandez P A et al. (2021) Psychological profiles in adults with knee OA-related pain: A replication study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 13, 1759720-211059614.

- 32.Johnson V L, Hunter D J. (2014) The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. , Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatol 28(1), 5-15.

- 33.Vina E R, Kwoh C K. (2018) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. , Curr Opin Rheumatol 30(2), 160-167.

- 34.C J Woolf. (1989) Recent advances in the pathophysiology of acute pain. , Br J Anaesth 63, 139-146.

- 35.Swift A. (2012) Osteoarthritis 1: Physiology, risk factors and causes of pain. , Nurs Times 108(7), 12-15.

- 36.Edwards R R, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite J A. (2011) Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. , Nat Rev Rheumatol 7, 216-224.

- 37.Cherif F, Zouari H G, Cherif W, Hadded M, Cheour M et al. (2020) Depression prevalence in neuropathic pain and its impact on the quality of life. , Pain Res Management

- 38.Hafkamp F J, J de Vries, Gosens T, den Oudsten BL. (2021) The relationship between psychological aspects and trajectories of symptoms in total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. , J Arthroplasty 36(1), 78-87.

- 39.Hafkamp F J, Gosens T, J de Vries, den Oudsten BL. (2020) Do dissatisfied patients have unrealistic expectations? A systematic review and best-evidence synthesis in knee and hip arthroplasty patients. , EFORT Open Reviews 5(4), 226-240.

- 40.Lowry V, Ouellet P, Vendittoli P A, Carlesso L C, Wideman T H et al. (2018) Determinants of pain, disability, health-related quality of life and physical performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis awaiting total joint arthroplasty. Disabil Rehabil. 40(23), 2734-2744.

- 41.DRB Tavares, Moça Trevisani VF, Frazao Okazaki JE, MV de Andrade Santana, Pinto A C et al. (2020) Risk factors of pain, physical function, and health-related quality of life in elderly people with knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. , Heliyon 6(12), 05723.

- 42.Zheng S, Tu L, Cicuttini F, Zhu Z, Han W et al. (2021) Depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis: risk factors and associations with joint symptoms. , BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1), 40.

- 43.Hill S, Dziedzic K S, Ong B N. (2010) The functional and psychological impact of hand osteoarthritis. , Chronic Illn 6, 101-110.

- 44.López-López A, Montorio I, Izal M, Velasco L. (2009) The role of psychological variables in explaining depression in older people with chronic pain. , Aging Ment Health 12, 735-745.

- 45.Axford J, Butt A, Heron C, Hammond J, Morgan J et al. (2010) Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool. , Clin Rheumatol 29, 1277-1283.

- 46.Howard K J, Ellis H B, Khaleel M A, Gatchel R J, Bucholz R. (2010) Psychosocial profiles of indigent patients with severe osteoarthritis requiring arthroplasty. J Athroplasty.

- 47.Rathbun A M, Schuler M S, Stuart E A, Shardell M D, Yau M S et al. (2020) Depression subtypes in individuals with or risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 72(5), 669-678.

- 48.Sayre E C, Esdaile J M, Kopec J A, Singer J, Wong H et al. (2020) Specific manifestations of knee osteoarthritis predict depression and anxiety years in the future: Vancouver Longitudinal Study of Early Knee Osteoarthritis. , BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21(1), 467.

- 49.Qiu Y, Ma Y, Huang X. (2022) Bidirectional relationship between body pain and depressive symptoms: A pooled analysis of two National Aging Cohort Studies. Front Psychiatry. 13, 881779.

- 50.Yelin E, Lubeck D, Holman H, Epstein W. (1987) The impact of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: the activities of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis compared to controls. , J Rheumatol 14, 710-717.

- 51.Okma-Keulen P, Hopman-Rock M. (2001) The onset of generalized osteoarthritis in older women: a qualitative approach. Arthritis Care Res. 45, 183-190.

- 52.Keefe F J, Caldwell D S, Queen K T, Gil K M, Martinez S et al. (1987) Pain coping strategies in osteoarthritis patients. , J Consulting Clin Psychol 55(2), 208.

- 53.Sarfraz R, Aqeel M, Lactao J, Khan S, Abbas J. (2021) Coping strategies, pain severity, pain anxiety, depression, positive and negative affect in osteoarthritis patients; A mediating and moderating model. , Nature-Nurture J Psychol 1(1), 18-28.

- 54.Broderick J E, Junghaenel D U, Schneider S, Bruckenthal P, Keefe F J. (2011) Treatment expectation for pain coping skills training: Relationship to osteoarthritis patients' baseline psychosocial characteristics. , Clin J Pain 27, 315-322.

- 55.Sharma S, Kumar V, Sood M, Malhotra R. (2021) Effect of preoperative modifiable psychological and behavioural factors on early outcome following total knee arthroplasty in an Indian population. , Indian J Orthop 55(4), 939-947.

- 56.Kopp B, Furlough K, Goldberg T, Ring D, Koenig K. (2021) Factors associated with pain intensity and magnitude of limitations among people with hip and knee arthritis. , J Orthop 25, 295-300.

- 57.Hawker G A, Gignac M A, Badley E, Davis A M, French M R et al. (2011) A longitudinal study to explain the pain‐depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. , Arthritis Care & Research 63(10), 1382-1390.

- 58.Sanftenberg L, Dirscherl A, Schelling J, Gensichen J, Voigt K et al. (2021) Quality of care in family practice and quality of life from the point of view of older patients with gon- and coxosteoarthritis - results from the MobilE-TRA cohort study. , MMW Fortschr Med 163(6), 19-26.

- 59.Jacobs C A, Mace R A, Greenberg J, Popok P J, Reichman M et al. (2021) Development of a mind body program for obese knee osteoarthritis patients with comorbid depression. , Contemp Clin Trials Comm 21, 100720.

- 60.Jacobs C A, Vranceanu A M, Thompson K L, Lattermann C. () Rapid progression of knee pain and osteoarthritis biomarkers greatest for patients with combined obesity and depression: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. , Cartilage 11(1), 38-46.

- 61.Lowry V, Bass A, Vukobrat T, Décary S, Bélisle P et al. (2021) Higher psychological distress in patients seeking care for a knee disorder is associated with diagnostic discordance between health care providers: a secondary analysis of a diagnostic concordance study. , BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1), 650.

- 62.Marks R. (2009) Physical and psychological correlates of disability among a cohort of individuals with knee osteoarthritis. , Can J Aging 26, 367-377.

- 63.Parmelee P A, Harralson T L, McPherron J A, Schumacher H R. (2012) The structure of affective symptomatology in older adults with osteoarthritis. , Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

- 64.Axford J, Heron C, Ross F, Victor C R. (2008) Management of knee osteoarthritis in primary care: pain and depression are the major obstacles. , J Psychosom Res 64, 461-467.

- 65.Vitiello M V, Zhu W, M Von Korff, Wellman R, Morin C M et al. (2022) Long-term improvements in sleep, pain, depression, and fatigue in older adults with comorbid osteoarthritis pain and insomnia. , Sleep 45(2), 231.

- 66.Hirsch J K, Altier H R, Offenbächer M, Toussaint L, Kohls N et al. (2021) Positive psychological factors and impairment in rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease: do psychopathology and sleep quality explain the linkage?. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 73(1), 55-64.

- 67.Carlesso L C, Jafarzadeh S R, Stokes A, Felson D T, Wang N et al. (2022) Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study Group. Depressive symptoms and multi-joint pain partially mediate the relationship between obesity and opioid use in people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage.

- 68.Ingegnoli F, Schioppo T, Ubiali T, Ostuzzi S, Bollati V et al. (2022) Patient perception of depressive symptoms in rheumatic diseases: a cross-sectional survey. , JCR: J Clin Rheumatol 28(1), 18-22.

- 69.Poon C L, Cheong P, Tan J W, Thumboo J, Woon E L et al. (2021) Associations of the modified STarT back tool and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) with gait speed and knee pain in knee osteoarthritis: a retrospective cohort study. , Disabil Rehabil 12, 1-7.

- 70.Mehta R, Shardell M, Ryan A, Dong Y, Beamer B et al.Persistency of depressive symptoms and physical performance in knee osteoarthritis.

- 71.Ribeiro I C, AMV Coimbra, Costallat B L, Coimbra I B. (2020) Relationship between radiological severity and physical and mental health in elderly individuals with knee osteoarthritis. , Arthritis Res Ther 22(1), 187.

- 72.Vogel M, Binneböse M, Lohmann C H, Junne F, Berth A et al. (2022) Are anxiety and depression taking sides with knee-pain in osteoarthritis?. , J Clin Med 11(4), 1094.

- 73.Ahn H, Weaver M, Lyon D, Choi E, Fillingim R B. (2017) Depression and pain in Asian and White Americans with knee osteoarthritis. , J Pain 18(10), 1229-1236.