Successful Aging, Social Isolation, and COVID-19: Do Restrictions Help or Hinder?

Abstract

Background

Aging, a commonly accepted time period of declining heath has been shown to vary in terms of its impact on function and independence.

Aims

This mini review examines the current impact of COVID-19 on the goal of ‘successful aging’, a conceptual model and outcome variable deemed desirable, but hard to attain.

Methods

Peer reviewed articles published between March 1 2020 and April 15 2021 focusing on ‘successful aging’ and COVID-19 secondary impacts, as located in the PUBMED data base were specifically sought.

Results

Despite a lack of consensus on the concept of ‘successful aging, and whether this can be achieved or not, ample evidence points to a severe secondary impact on efforts to age as successfully as possible by older adults, especially those isolated in the community as a result of lockdowns.

Conclusion

Pursuing more efforts to counter predictable harmful cognitive as well as physical impacts of lockdowns, resource and movement restrictions is urgently needed.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2021 Ray Marks

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

The quest for a means of allaying or limiting age-associated declines in health and prowess has been pursued for some time, with marginal success. This quest, which continues in the hope of fostering the well-being of all citizens, including physical, mental, and social health factors, as well as engagement in life affirming activities, appears highly desirable in efforts to attain optimally healthy and functional aging societies. However, the unanticipated and abrupt emergence of the coronavirus disease known as COVID-19 has undoubtedly decimated the health and well-being opportunities of many older highly vulnerable adults in all parts of the world since December 2019 1, 2, 3. At the same time, and despite the anticipated functional as well as cognitive declines among the survivors of COVID-19, which are expected to unfold more distinctively, in the ensuing post pandemic period, and that would clearly have a strong bearing on the ability to age ‘successfully’, efforts to allay this sequence of potentially highly adverse events are not commonly forthcoming to any degree, given the acute and persistent need to focus public health efforts on mitigating the unrelenting pandemic through social isolation, restrictions, and vaccination 4.

But is this highly selective primary preventive strategy aimed at preventing excess deaths and hospital utilization fraught with unforeseen health and social consequences?

To address this possible and future emergent negative possibility, and to offer some guidelines for averting any further excess health burden on the elderly, as well as societies, this current mini review aimed to shed some insight on this topic focus by examining some of the findings concerning the implications of COVID-19 associated restrictive personal as well as resource related lockdowns or closure rulings and their independent or possible collective future impact on efforts for community dwelling older adults to age successfully, in the event societies fail to consider the evidence. In particular, the discourse aimed to examine the degree of support for the idea that a failure to counter the possible negative impacts of excess lockdowns on older community dwelling adults on overall stress and wellbeing, including economic, sleep, immune system and social health stresses may prove more costly than not. To this end, some intervention ideas are also discussed, including those that might potentially impact overall health status and/or the genetically programmed process of death and debility associated with aging in a favorable manner. Since the concept of optimum health for all is an acceptable current public health goal, and may highly depend on the older adult’s ability to engage actively and continuously in meaningful life events 5, it appears reasonable to continue to examine whether the goal of aging well or ‘successfully’ is likely to be in jeopardy or not, in spite of the ongoing goal of multiple COVID-19 lockdown and social measures and restrictions to save lives.

Since perceptions of successful aging may impact health status 5, a key COVID-19 risk and outcomes determinant, and social distancing is aligned with negative affect and other consequences 6, the key aim of this review was to evaluate if there is reasonable support for efforts to expand upon current restrictive health recommendations to not only secure the safety of older community dwelling adults, regardless of setting, but also to heighten their overall health. Community dwelling older adults are examined as they may not only suffer isolation, but highly limited access to needed resources and personnel, otherwise obtainable in the nursing home.

Methods

To this end, only recently published peer reviewed data on this topic, located in the PUBMED data base over the time periods December 2019- April 2021 using the key search terms of: successful aging, lockdowns, social isolation, immune system, and COVID-19 were sought. Those articles that focused on the concept of ‘successful aging’ and the impact of COVID-19 on older adults living in the community and affected by lockdown strategies that might limit their ability to age successfully, in the absence of any targeted counter strategies were specifically sought and examined. Possible remedies in this regard were also noted. All forms of publication were deemed acceptable, and those deemed most relevant were carefully scrutinized to obtain a sense of their content, salience, and implications.

Results

Overall Findings

The literature search and the material extracted from that search, while not necessarily representing all publications in the field, yielded 1244 stand alone articles on ‘successful aging’, 49 PUBMED research reports on ‘successful aging and COVID-19’, plus 15 on ‘lockdowns’ and aging, 43 on the ‘immune system and social isolation’. The posted research and reviews were highly diverse, however, and attempts were hence made as a result to narrow the current search and discussion primarily to the social and emotional impacts of lockdowns on overall life quality among older freely living adults desiring to age in place.

This idea was based on a study of the experiences of older people by Heid et al. 7 who found the experiences appraised as most difficult by participants fell into 8 domains: Social Relationships, Activity Restrictions, Psychological, Health, Financial, Global Environment, Death, and Home Care. The most frequently appraised challenges moreover, were constraints on social interactions (42.4%) and restrictions on activity (30.9%). However as pointed out by Burlacu et al. 4 epidemiological arguments favoring self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic are widely recommended, while the consequences of social isolation/loneliness of older people considered to be at higher risk for severe illness are neglected, even while they are disproportionately affected. In addition, as outlined by Lim et al. 8 it is important to not only evaluate the impacts of COVID-19 on older people, but to potentially balance the successful pandemic control of COVID-19 with active with proactive management approaches to avert current as well as future negative albeit modifiable secondary and negative health outcomes and their possible undesirable consequences.

In this regard, Yeung et al. 5 imply that comprehensive efforts to promote successful aging perceptions, despite lockdown restrictions, are more likely than not to be helpful in fostering adequate levels of physical and psychosocial functioning, as well as higher resilience levels, affective signs of wellbeing and fewer depressive symptoms, along with heightened rates of premature mortality. Moreover, research indicated that older adults who exhibit adaptive rather than maladaptive regulatory behaviors are more likely to be able to regulate their emotions and proactively deal with future stressors, the occurrence or persistence of negative events or potential losses in response to the pandemic.

However, achieving this state may be especially challenging if key mental and physical health determinants are compromised in the context of social distancing imperatives that prevail for COVID-19 to a high degree 6, 9.

Social Isolation Impacts

As outlined in the current literature, the widespread lockdowns that persist in 2021 and that have imposed extended periods of social isolation quite unexpectedly as an outcome of multiple socially restrictive pandemic rulings to avert infection and fatalities, may prove especially challenging for many older adults in the community who either live alone or are less able than others to live independently, while being denied resource access, and others, especially in the medical sphere 10, 11. As well, excess loneliness and fears that have been engendered 12, may not only impact mental wellbeing quite markedly, regardless of overall health status and age, but physical wellbeing, as well as cognitions, which are all important analogues of ‘successful aging’. Those who have limited economic and technical resources, along with those who have become increasingly frail or debilitated are in turn, more likely than not to succumb to COVID-19 infections, especially if they feel a threat to their mental and physical health directly tied to their quarantine and restricted state as outlined by Daly et al. 13. Their emotionally charged and declining activity based participation, could also be expected to impact unfavorably on many body systems, thus raising the risk of incurring one or more chronic diseases, or increasing their concurrent severity, and thereby, all cause mortality rates that could rival clinical factors, such as obesity 11.

As discussed by Acquisto and Hamilton 14, this persistent imposition of physical and social restrictions, and a pervasive inability of the older home bound adult to interact socially with important others, both formal, as well as informal, is likely to affect the body quite negatively and substantively in a threefold manner, that is at the physiological, psychological, and behavioral levels. Unsurprisingly, social isolation in its own right, may be an independent risk factor for obesity and others harmful physiological states, as well as excess weight loss and frailty. In addition, excess feelings of depression, and lack of direct care access, may heighten the need for pain killing drugs and harmful addictive substances 12. Loneliness, a potential consequence of being forced to socially distance without respite, is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, a key risk factor for COVID-19 disease.

It is no surprise therefore that Labreusseur et al. 15 who recently examined 135 publication records related to COVID-19 found the presence of psychological symptoms, the exacerbation of ageism, and the physical deterioration of aged populations to be quite common. As well, decreases in social life events and interactions reported during the pandemic were occasionally associated with a reduced life quality and increased feeling of depression. Difficulties accessing services, sleep disturbances and a reduction of physical activity were also noted.

As related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Kotwal et al. 16 found those elderly participants they interviewed to have experienced social isolation in 40% of cases, while 76% reported minimal video-based socializing, and 42% reported minimal Internet-based socializing. In addition, socially isolated participants reported difficulty finding help with functional needs including bathing (20% vs 55%; P = .04), and more than half (54%) of the participants reported worsened loneliness due to COVID-19 that was associated with worsened depression (62% vs 9%; p < .001) and anxiety (57% vs 9%; p < .001). Although loneliness ratings declined on average over time for some, loneliness persisted or worsened for a substantive subgroup of participants. Open-ended responses revealed challenges faced by this subgroup to include signs of poor emotional coping and discomfort with new technologies.

In addition to depression, Herron et al. 17 found that older adults' experiences of isolation and loneliness in the initial stages of the pandemic between the months of May and July 2020 were accompanied by feelings of a loss of autonomy, activities and social spaces (e.g., having coffee or eating out, volunteering, and going to church), as well as a lack of meaningful connections at home as factors influencing their sense of isolation and loneliness. Based on prior research, this reduced ability to be able to foster a meaningful existence, in the absence of social support, and contacts, may be expected to further foster painful and depressive experiences that reduce the will towards activity, as well as impacting immune health adversely. By contrast, where moderate support exists, along with opportunities for greater physical activity and more social contacts and participation, better physical and mental health attributes are likely to follow.

As such, Joffe 1 notes that the response to COVID-19 lockdowns may indeed be far more harmful to the wellbeing of older adults, and others than COVID-19 itself, regardless of health status. Activities that may be severely impacted and that can be considered to be life affirming when enabled are voluntary activities/work in the community, freedom to independently shop and take transport, freedom to interact with family members and others, plus freedom to obtain personal health services and counseling as required 18. To the contrary, social self-isolation, and distancing coupled with lockdowns of community resources and opportunities, which are unlikely to markedly impact current 2021 COVID-19 infection rates to a high degree 18, will potentially impact older adults’ ability to age well, as well as to offset COVID-19 risk, even if many older adults currently under lockdown remain uninfected.

Social Isolation and the Immune System

Compelling data concerning social isolation that do exist, clearly indicate that a lack of adequate social contact and support produces the down regulation of the immune system, along with stress response genes and behavioral changes as identified in the context of basic studies of insects. While not directly related to humans, these data are undoubtedly highly relevant to consider in efforts to minimize any potentially analogous effect of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on the older socially isolated adult. These negative responses, said to be attributable to deleterious alterations in neural circuitry, may inadvertently not affect their motivation and/or ability to pursue necessary preventive behaviors against COVID-19, but may lower the already compromised immune responses of many aging adults and with this, excess premature mortality rates, and hospitalizations 5. As examined by Scharf et al. 19 humans and other social mammals that experience isolation from their group tend to report this as stressful, as well as exhibiting behavioral and physiological anomalies that reduce fitness. An impaired ability to interact socially, can also impact changes in stress tolerance, gut-immune-brain axis mechanisms, a suite of physical and psychological health issues, and immune competence as verified by Donovan et al. 20 in an animal model where social isolation increased anxiety-like behaviors and impaired social affiliation. Isolation also resulted in sex- and brain region-specific alterations in neuronal activation, neurochemical expression, and microgliosis, as well as possible immune system weakness and frailty 21. According to Lozupone et al. 21 even the perception of social isolation such as loneliness, affects mental and physical health, as well as the integrity of the immune system, and has multiple associated cognitive and health-related sequelae. Hence, the currently reduced sources of support, along with heavy demands on personal resources, plus loneliness may be a factor associated with psychological distress and an undesirable set of outcomes in their own right in addition to increased COVID-19 susceptibility.

As per Du Preez et al.. 22 chronic stress can not only alter the immune system, as well as adult hippocampal neurogenesis and induce anxiety, but also depressive-like behavior. It can also impact immunity indirectly through its effect on sleep 23. This is because, social isolation, including the need to self-quarantine, the restricted mobility and social contact rules, and possible concerns about resource availability, fear of infection, questions about the duration of self-quarantine, can not only cause anxiety and depression, as well as stress, but insomnia or sleep quality and quantity changes, that may present a greater risk to the health of the individual than the virus alone, as this may aggravate systemic and lung inflammation during viral infections or induce harmful pro-inflammatory states, increased vulnerability to viral infections, and oxidative/antioxidant imbalances.

As outlined by Mattos Dos Santos et al. 24 social disruption stress may not only impact the functioning of the immune system, but it may cause several stress hormones evolved to defend against physical injury during periods of heightened risk to be released. While protective to some degree, if prolonged, these responses could leave the organism vulnerable to viral infections, as well as increases in pro-inflammatory gene states, while suppressing anti-viral gene expression. This series of alterations in transcriptional status is reportedly related to conditions of social stress, either through the presence of any hostile human contact, or increased predatory vulnerability due in part, to separation from the social group.

Raony et al. 25 indicate that for the above reasons and others, the impacts of the coronavirus 19 disease may go well beyond that of the respiratory system, also greatly affecting mental health, as well as coping responses, and perceptions of successful aging that impact these emotional responses 5. In addition to inaccurate or exaggerated perceptions and beliefs, and their emotional responses, that may mediate a possible association between COVID-19 and psychiatric outcomes, are fears evoked by the media, as well as those inherent in the context of the pandemic, the possible adverse effects of non personalized treatments or their absence, as well as financial stresses, excess physical stress, loneliness, sleeplessness, and further social isolation. This group also explored whether the relationship between COVID-19 and the host may also trigger more permanent changes in brain and behavior, such as neuroendocrine-immune changes, given evidence that social isolation and loneliness, can be shown to heighten unwanted chronic inflammatory responses 26.

As per Yeung et al. 5 the overlapping issues of social distancing, including the temporary closure of public entertainment places, such as theatres and fitness centers, as well as health resources, and others, along with the high perceived uncertainty and susceptibility among local resident because of the lack of information, conflicting information, and inability to possibly cope independently at best has been found to precipitate panic and anger, while considerably interrupted work arrangements if applicable, as well as key life affirming social relationships.

Social Isolation Health Challenges and Successful Aging

Although positive perceptions of ‘successful aging’ are found to impact the wellbeing of older adults more favorably than not 5, favorable perceptions of wellbeing that predict ‘successful or healthy aging’ may be highly challenging to achieve. Indeed, the effects of lockdowns on mental health, along with a possible loss of personal efficacy or control, as well as valued and essential activities including opportunities for older isolated adults to interact and partner with empathetic formal and informal providers and caregivers directly is likely to induce a highly undesirable array of negative emotional, social, and physical impacts that might be irreversible. Moreover, in failing to partner with older adults and to understand their particular social needs and others, policy makers, may find more distress being engendered than desirable among this group 33, especially where fear based technical messages persistently abound, rather than culturally tailored informative resources, and clear options, in different formats and languages. Moreover, rather than hoping technology or robots 11 will be sufficiently helpful in overcoming the repercussions of lockdowns in the older community dwelling adults, regardless of level of ability or disability, a dedicated focus on the provision of carefully construed comprehensive holistic care strategies appears strongly indicated. This includes, but is not limited to the safe provision of required life-affirming forms of social support 27, opportunities to enjoy sound nutrition practices, an active lifestyle, peer support specialists and support groups, and counseling 28. As well optimizing desirable environmental factors, including those that promote moderate physical activity, could make an immense difference in all likelihood to the success of any government policy in the fight against COVID-19, as well as securing the long-term well-being and ‘successful aging’ of its older community living population 29.

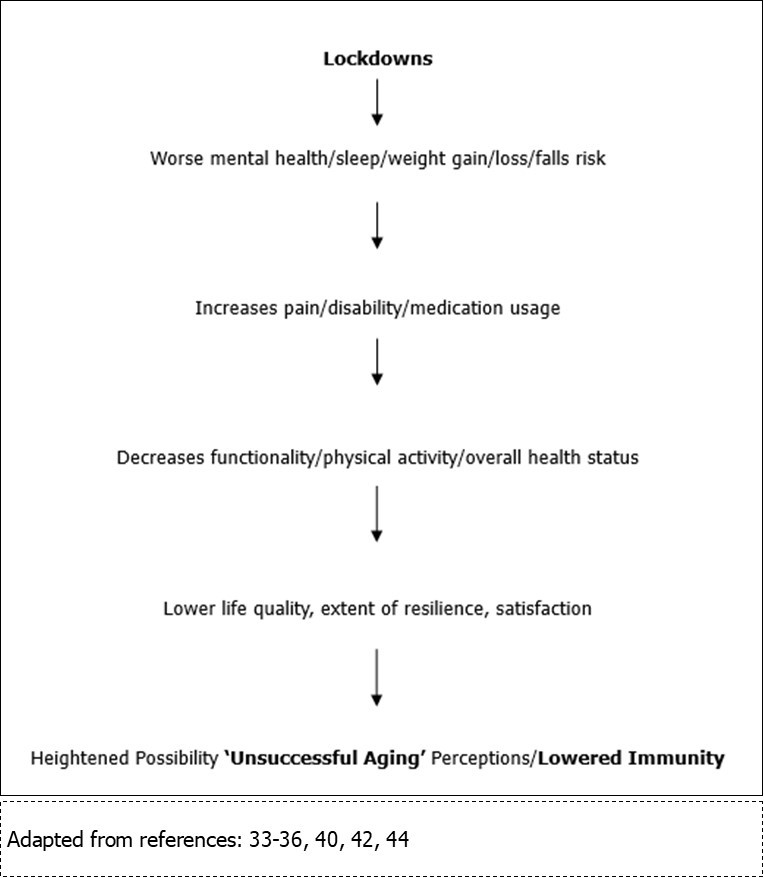

Alternately, as per Figure 1, despite their ‘laudable intentions’, it is highly possible that lockdown and distancing regulations designed to mitigate the spread and acquisition of COVID-19 among older community dwelling elderly adults and others, may indeed result in unanticipated as well as overwhelming multiple undesirable health outcomes 14, if the role of other health determinants and the importance of social factors in this regard is largely ignored. Moreover, the prolonged absence or inaccessibility for many community dwelling older adults to consistent, timely, empathetic and compassionate care, and needed medical and surgical attention, and a temporary replacement of desired personal counselling services with online social media and technological strategies may fail to provide an optimal substitute or viable solution to health issues other than COVID-19 that require attention. This situation is likely to be especially dire in the event the individual cannot effectively and proactively contribute to their own well-being independently in real time and on a consistent basis, or they have limited literacy, needed resources, and technical skills. Moreover, even if this set of determinants is not an issue, the ability to manage one’s health condition optimally in the face of travel restrictions, cuts in services, unknown time lines, and others can be expected to have an additionally negative individual and collective impact. In particular, poor health stemming from artificially imposed social restrictions may not only heighten COVID-19 risk 14, but it may engender cardiovascular disease, the number one killer, while hastening mental health declines 30. Isolation and lockdowns may also be expected to exacerbate current health problems 30 such as, obesity, depression, and frailty.

Figure 1.Conceptual Model of Interactive Outcomes of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Successful Aging

On the other hand, carefully construed parallel initiatives to assist vulnerable older adults under lockdown to receive needed support as soon as possible may combat this host of adverse social isolation associated impacts to a high degree. In particular, efforts to assist older adults with any required home modifications, certain forms of equipment, plus personalized home health care visits and phone calls, safe access to gyms, community based centre and religious resources, peers, local shops, and others as indicated, may be especially helpful in averting declining health outcomes 31 and COVID.

Discussion

By 2030, the numbers of older adults worldwide is anticipated to rise substantively. However, while many older adults today will live to become centurions, many who are alive today, may not reach their optimal potential at all successfully, if the pandemic associated precautionary social distancing rules, restrictions, ordinances, and others are not compensated for or minimized in the population of older adults in a meaningful way as soon as possible.

To the contrary, the prevailing widespread socially restrictive initiatives designed to preserve life and wellbeing, may not only reduce those key attributes of resilience and the ability to achieve personally valued goals 40, upon which the idea of ‘successful aging’ is conceptualized, but the multiple ongoing restrictions may produce feelings of fear, depression and distress that impede desirable self management practices, including the key importance of physical activity practices 36.

Moreover, since ‘successful aging’ is partially premised on five key categories of perception: including social wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, physical health, spirituality and transcendence, plus environmental and economic security 37, any disconnect between these desirable attributes amidst any long-term socially limiting COVID-19 isolating imperatives may well foster a host of negative repercussions Figure 1. As such, disruptions in the attributes of social cohesion and resource availability, plus perceptions of a strong sense of community, which are vital health promoting elements 46, which may decline, may be expected to adversely impact those aspects of well-being that are deemed key to ‘aging well’, and being able to minimize adverse feelings of despair, fear, stress, depression, anxiety, loneliness and lack of meaning that can heighten COVID-19 risk as well as exacerbate or foster one or more chronic health conditions, especially those linked to COVID-19, such as obesity, and cardiovascular disease 44. Alternately, placing more emphasis on what is most important as well as required by the individual older adult – in light if their unique personal needs and situation, and perhaps helping them to feel their artificially imposed socially restrictive situation is actually ‘helpful’ and a contribution to many others 43, even if it is emotional draining, can surely in turn, promote their sense of personal efficacy and worth, despite being lonely and isolated. It is also probable that drawing on the ‘strengths’ of the older adult and helping them to proactively attempt to maintain a full and independent life by means of their own efforts over the currently stressful pandemic period, coupled with efforts to combat loneliness 38, may further prevent excess debility, while promoting regenerative or reparative states, where the individual may feel very satisfied and thus successful-all things considered. To the contrary, if nothing is done to translate and apply evidence supporting primary prevention strategies, implemented immediately, to foster an optimally safe, as well as supportive and enriching living environments, offsetting the prevalence as well as the severity of COVID-19 and comorbid health complications through isolation alone seems unlikely 14, 15.

These strategies may include, but are not limited to home adaptations to limit falls injuries often due to secondary depression 34, the provision of an adequate nutritious food supply 36, medication oversight, opportunities for modest exercise 36, and companionship 38. Moreover, these efforts should be sustained, rather than short-lived to avert long-term potentially preventable decrements in health 36. To this end, more marketing and advocacy by aging foundations as to why it is imperative to protect older adults who are presently confined inadvertently in efforts to protect them against COVID-19 is strongly recommended. As well, to avert unwanted declines in health status among older homebound adults, especially physical and psychosocial declines 12 among women who live alone 46, more expert guidance and other efforts by physicians and clinicians to help combat or prevent excess depression and anxiety and improve coping skills in this group using diverse communication strategies, will undoubtedly be very helpful in advancing those perceptions of personal efficacy that foster motivation for self-protection and well-being, despite being exposed to multiple COVID-19 related risks 2, 33, 35, 46, 48. By contrast, although not well studied or incorporated into current modeling analogies, a pervasive focus on the immense importance of extended lockdowns, social distancing, isolation, and pauses in community services and activities, may be expected to be place high numbers of older adults at risk for both current as well as poor future health and excess mortality rates and morbidity rates, as well as limiting their ability to overcome remediable current health challenges. Indeed, even if life returns to ‘normal’ and older adults in the community remain unaffected directly by COVID-19 infections, it appears that as the lockdown, social distancing, and stay at home orders persist, society will experience extremely high potentially preventable social and economic costs 40. Older adults with disabilities as well as multi morbidities are especially likely to incur high rates of excess suffering owing to any prolonged and unexpectedly imposed isolating socially and emotionally impactful stress related social disruptions,and ordinances 36, 41, and dissatisfaction with communication situations 47, unless preferentially and thoughtfully targeted in a timely compassionate way 48.

In this regard, and to mitigate potentially catastrophic health and social outcomes for societies post COVID-19 of excessively stressful negatively impactful lockdowns 47, several promising ideas have been put forth that appear worthy of consideration. Among those are active rather than passive strategies designed to build resilience 38, 40, 45, as well as appropriate strategies to minimize any excess psychological suffering, stress and anxiety, unmet medical needs of those experiencing persistent loneliness 6, and required financial assistance 49. Since desirable social communication opportunities are found to buffer loneliness 47, barriers to technology-based social interaction 16 as well as physical activity barriers 6, along with other barriers to maintaining optimal mental, nutritional, and social well-being also need to be addressed 15, 39, 49, regardless of health status 40.

As well, carefully examining whether the negative consequences of large-scale lockdowns are effective or not should receive due consideration 50

Conclusion

Older community dwelling adults may be impacted negatively by commonalities related to life style, cognitions, and behaviors that stem from loneliness, social isolation, and deficits in social support, social cohesion, and social networks consequent to prolonged and highly stressful preventive COVID-19 lockdown ordinances.

To eliminate burdening the health care system in the future, and help older adults to age as successfully as possible in the interim, concurrent strategies to mitigate COVID-19 spread, as well as more comprehensive proactive strategies to foster psychosocial wellbeing of community elders are clearly imperative.

References

- 2.Giebel C, Ivan B, Ddumba I. (2021) COVID-19 Public health restrictions and older adults' well-being in Uganda: Psychological impacts and coping mechanisms. , Clin Gerontol. Apr 12, 1-9.

- 3.Sayin Kasar K, Karaman E. (2021) Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVİD-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Geriatr Nurs.

- 4.Burlacu A, Mavrichi I, Crisan-Dabija R, Jugrin D, Buju S. (2020) Celebrating old age": an obsolete expression during the COVID-19 pandemic? Medical, social, psychological, and religious consequences of home isolation and loneliness among the elderly. , Arch Med Sci 17(2), 285-295.

- 5.Yeung D Y, EKH Chung, AHK Lam, Ho A K. (2021) Effects of subjective successful aging on emotional and coping responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. , BMC Geriatr 21(1), 1-11.

- 6.Heidinger T, Richter L. (2020) The effect of COVID-19 on loneliness in the elderly. An empirical comparison of pre-and peri-pandemic loneliness in community-dwelling Elderly. Front Psychol. 30, 1-5.

- 7.Heid A R, Cartwright F, Wilson-Genderson M, Pruchno R. (2021) Challenges experienced by older people during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. , Gerontologist 61(1), 48-58.

- 8.Lim W S, Liang C K, Assantachai P, Auyeung T W, Kang L. (2020) COVID-19 and older people in Asia: Asian Working Group for sarcopenia calls to actions. , Geriatr Gerontol Int 20(6), 547-558.

- 9.Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Rodríguez-Sánchez I, Pérez-Rodríguez P, Ganz F, Torralba R.Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. , J Nutr Health Aging 24(9), 938-947.

- 10.Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W, Bohlken J, Kostev K. (2021) Effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on disease recognition and utilisation of healthcare services in the older population in Germany: a cross-sectional study. , Age Ageing 50(2), 317-325.

- 11.Jecker N S. (2020) You've got a friend in me: Sociable robots for older adults in an age of global pandemics. , Ethics Inf Technol. Jul 16, 1-9.

- 12.Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey M. (2020) . Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14(5), 779-788.

- 13.Daly J R, Depp C, Graham S A, Jeste D V, Kim H C. (2021) Health impacts of the stay-at-home order on community-dwelling older adults and how technologies may help: Focus group study. , JMIR Aging 4(1).

- 14.D'Acquisto F, Hamilton A. (2020) Cardiovascular and immunological implications of social distancing in the context of COVID-19. Cardiovasc Res. , Aug 116(10), 129-131.

- 15.Lebrasseur A, Fortin-Bédard N, Lettre J, Raymond E, Bussières E L. (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on older adults: A rapid review. , JMIR Aging. Mar 10.

- 16.Kotwal A A, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark R L, Cenzer I, Smith A K. () Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay Area older adults during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders. , J Am Geriatr Soc 69(1), 10-1111.

- 17.Herron R V, NEG Newall, Lawrence B C, Ramsey D, Waddell C M. (2021) Conversations in times of isolation: Exploring rural-dwelling older adults' experiences of isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba. , Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Mar 18(6), 1-14.

- 18.Richter L, Heidinger T. (2020) Caught between two fronts: Successful aging in the time of COVID-EmeraldL24 (4). Working with Older People.https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/WWOP-06-2020-0031/full/html.

- 19.Scharf I, Stoldt M, Libbrecht R, Höpfner A L, Jongepier E. (2021) Social isolation causes downregulation of immune and stress response genes and behavioural changes in a social insect. Mol Ecol.

- 20.Donovan M, Mackey C S, Platt G N, Rounds J, Brown A N. (2020) Social isolation alters behavior, the gut-immune-brain axis, and neurochemical circuits in male and female prairie voles. , Neurobiol Stress. Nov 24, 1-21.

- 21.Lozupone M, La Montagna M, I Di Gioia, Sardone R, Resta E. (2020) Social frailty in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Front Psychiatry. 3, 1-8.

- 22.Du Preez A, Onorato D, Eiben I, Musaelyan K, Egeland M. (2021) Chronic stress followed by social isolation promotes depressive-like behaviour, alters microglial and astrocyte biology and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice. , Brain Behav Immun. Jan; 91, 24-47.

- 23.Mello M T, Silva A, Guerreiro R C, da-Silva F R, Esteves A M. (2020) Sleep and COVID-19: considerations about immunity, pathophysiology, and treatment. , Sleep Sci 13(3), 199-209.

- 24.R Mattos Dos Santos. (2020) Isolation, social stress, low socioeconomic status and its relationship to immune response. in Covid-19 pandemic context. Brain Behav Immun Health. Aug;7: 1-6.

- 25.Raony Í, de Figueiredo CS, Pandolfo P, Giestal-de-Araujo E. (2020) Psycho-neuroendocrine-immune interactions in COVID-19: Potential impacts on mental health. Front Immunol. 27, 1170-10.

- 26.Koyama Y, Nawa N, Yamaoka Y, Nishimura H, Sonoda S. (2021) Interplay between social isolation and loneliness and chronic systemic inflammation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Results from U-CORONA study. , Brain Behav Immun 94, 51-59.

- 27.Simpson V, Edwards N, Kovich M. (2021) Conversations about wellness: A qualitative analysis of patient narratives post annual wellness visit. , Geriatr Nurs. Apr 42(3), 681-686.

- 28.Mbao M, Collins-Pisano C, Fortuna K. (2021) Older adult peer support specialists' age-related contributions to an integrated medical and psychiatric self-management intervention: Qualitative study of text message exchanges. , JMIR Form Res 5(3), 1-7.

- 29.Angelini S, Pinto A, Hrelia P, Malaguti M, Buccolini F. (2020) The "elderly" lesson in a "stressful" life: Italian holistic approach to increase COVID-19 prevention and awareness. , Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11, 1-7.

- 30.Trivedi H, Trivedi N, Trivedi V, Moorthy A. (2021) COVID-19: The disease of loneliness and solitary demise. , Future Healthc J. Mar; 8(1), 164-165.

- 31.Lekamwasam R, Lekamwasam S. (2020) Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on health and wellbeing of older people: A comprehensive review. , Ann Geriatr Med Res 24(3), 166-172.

- 32.Lu Y, Matsuyama S, Tanji F, Otsuka T, Tomata Y. (2021) Social participation and healthy aging among the elderly Japanese: The Ohsaki Cohort. , Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci

- 33.Batsis J A, Daniel K, Eckstrom E, Goldlist K. (2021) Promoting healthy aging during COVID-19. , J Am Geriatr Soc 69(3), 572-580.

- 34.Das Gupta D, Kelekar U, Rice D. (2020) Associations between living alone, depression, and falls among community-dwelling older adults in the US. Prev Med Rep. 2020, 101273.

- 35.Makizako H, Nakai Y, Shiratsuchi D, Akanuma T, Yokoyama K. (2021) Perceived declining physical and cognitive fitness during the COVID-19 state of emergency among community-dwelling Japanese old-old adults. , Geriatrics Gerontol Int 21(4), 364-369.

- 36.Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S, Sadoff S. (2021) Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. , Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Mar 118(9), 10-1073.

- 37.Zanjari N, Sharifian Sani M, Chavoshi M H, Rafiey H, Mohammadi Shahboulaghi F. (2017) Successful aging as a multidimensional concept: An integrative review. Med J Islam Repub Iran.

- 38.Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. (2020) Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc Sci Med. 265, 1-6.

- 39.Carriedo A, Cecchini J A, Fernandez-Rio J, Méndez-Giménez A. (2020) COVID-19, Psychological well-being and physical activity levels in older adults during the nationwide lockdown in Spain. , Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28(11), 1146-1155.

- 40.Chen L K. (2020) Older adults and COVID-19 pandemic: Resilience matters. , Arch Gerontol Geriatr 89, 104-124.

- 41.Dos Santos CF, Picó-Pérez M, Morgado P. (2020) COVID-19 and Mental Health-What Do We Know So Far? Front Psychiatry. 11, 1-6.

- 42.Tuason M T, Güss C D, Boyd L. (2021) Thriving during COVID-19: Predictors of psychological well-being and ways of coping. , PLoS One. Mar 16(3), 1-19.

- 43.Mitchell E, Walker R. (2020) Global ageing: successes, challenges and opportunities. , Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 81(2), 1-9.

- 44.Singh K, Kondal D, Mohan S, Jaganathan S, Deepa M. (2021) Health, psychosocial, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with chronic conditions in India: a mixed methods study. , BMC Public Health 21(1), 1-15.

- 45.Zapater-Fajarí M, Crespo-Sanmiguel I, Pulopulos M M, Hidalgo V, Salvador A. (2021) Resilience and psychobiological response to stress in older people: The mediating role of coping strategies. , Front Aging Neurosci 13, 1-15.

- 46.García-Portilla P, L de la Fuente Tomás, Bobes-Bascarán T, Jiménez Treviño L, Zurrón Madera P. (2020) Are older adults also at higher psychological risk from COVID-19?. Aging & Mental Health. 1-8.

- 47.Macdonald B, Hülür G. (2021) Well-Being and loneliness in Swiss older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social relationships. , Gerontologist. Feb 61(2), 240-250.

- 48.Siette J, Dodds L, Seaman K, Wuthrich V, Johnco C. (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of older adults receiving community-based aged care. , Australas J Ageing 40(1), 84-89.