Systematic Review on Peri-Operative Intravenous Fluid: ‘Restrictive vs Liberal’ Fluid use on Major Abdominal Surgical Patients

Abstract

Background

Intravenous Fluids use during surgery is a common practice for many reasons. However recent evaluation of perioperative abdominal surgery patients have poised many issues. Mostly on the type of fluid and quantity of volume usage on major abdominal surgery. Many studies into this aspect of perioperative fluid usage have been done, and volume definition have been accrued either restrictive (Maintenance fluid of less than 1.75 Liters) or liberal or standard (Maintenance fluid between 1.75 Liters to 2.75 Liters) usage. The outcome was assessed to ascertain the best patient recovery without complications from the two fluid regime.

Result/Discussion

After PRISMA exclusion criteria, there were eight randomized control studies assessed to provide a summary, comparing all the studies using either restrictive fluid or liberal fluids used in major abdominal surgery. Post operative complications and the length of hospital stay were assessed as the major outcomes end points and the cumulative result favored those with restrictive fluid usage.

Conclusion

Although the restrictive use of fluids in abdominal surgery is favored from the measured outcomes, there are inherent cofounders and heterogenicity in the eight studies that require more detail studies involving multiple study centers and population.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: John Bebawy, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Arnold Waine, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

The development of Intravenous fluid initially was to replace intraluminal volume deficiency among the patients with cholera1, 2.In current clinical practices, its use in the perioperative setting is a common practice among anesthetist and surgeons. It is use for replacing the fluid deficit after fasting, or to fill up intravascular volume after vaso-dilatational hypotension for spinal anesthesia or most commonly use in replacing blood loss during surgery14, 59.

Thomas Latta and O’Shaughnessy administer large volume of Intravenous fluid (IVF) to patients affected by Cholera more than a century ago3, 5. The composite was very basic with more fluid than electrolyte. It was aim to replace dehydration from diarrhea3, 4. Addition of inorganic electrolytes was later developed by Sydney Ringer in 1880 now refers to as the Ringers solution6, 7. Further success was done when Alexis Hartmann added sodium lactate to the Ringers solution to treat children with diarrhea8. Further research on Intravenous fluid development has seen solution containing sugar9and even colloid solution were introduced into the clinical practice10. Modern practice on peri-operative intravenous prescription has seen more uses with different types of fluid in different clinical settings.

During the last decade, several clinical studies have shown the necessity to administer appropriate intravenous fluid to support patients throughout the perioperative period. It was only after national enquiry in to perioperative deaths in London53that has shown an association of IVF related morbidity and mortality. It prompted the debate regarding the ideal quantity of intravenous fluid and the type of the IVF to be administered to the surgical patients.

Different randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been done looking at the effects of different fluid regimes on outcome of elective open abdominal surgery was published. These trials use different terminology to describe both volume and content of IVF. Amount of fluids are either liberal (standard) and restrictive fluids. Type includes colloid and crystalloid and balanced and unbalanced solution for the crystalloid solution. According to textbook recommendation for intra-operative fluid administration in patient undergoing intra-abdominal operation, fluid range should be 10-15ml/kg/hr54, 55, 56. Further suggestions were made that fluid regime with a 12-15 ml/kg for the first hour and 6-10 ml/kg for the next 2 hours during surgery57. It is also noted that during major surgery, intra operative cardiovascular stability is better achieved with crystalloid at a rate of 10-15ml/kg/hr58.

In 2009, Guidelines for Intravenous Fluid Therapy for Adult Surgical Patients (GIFTASUP) was proposed to stratify and standardized the use of fluids and electrolytes in different centers in Europe11For a adult surgical patient, maintenance IVF would get a total volume of balance solution of 1.75L to 2.75L per day, Sodium is 50 -100 mmol/L and Potassium is 40- 80mmol/L per day. However, the evidence level at which this fluid regime derived was level 5. Fluid received by patient within this range was defined as balance. Less than 1.75 Liters was regarded as restricted fluid therapy and Liberal or overload if the amount was more than 2.75 Litres13. Even decades of careful clinical studies, optimal fluid management still remains an individual judgment given the complexity of the patho-physiology and wide ranges of surgical stress17. Therefore a definite universal formula cannot be established for the use of IVF in surgery. Hence perioperative fluid management is still an ongoing debate. However, the ideal goal for perioperative fluid therapy is to restore and maintain normal physiology, blood volume and organ function14, 15whilst maintaining a zero fluid balance and minimal weight gain16, 17.

Until now, we don’t know what maintenance fluid regime (type and volume) is best administer during major abdominal surgery to achieve best post operative recovery with less complication and shorter hospital stay. So the aim of this systematic review was to perform a meta-analysis of RCT on perioperative intravenous fluid use on patient undergoing major elective abdominal surgery, and to know either restrictive or liberal (standard) use of fluid shows better perioperative outcomes.

Methods

Definitions

Intravenous fluid therapy for surgical patients should be optimal. The required optimal range is however narrow and by giving too much or too little fluid can result in adverse outcome16, 17, 18. An adult surgical patient without any ongoing losses or deficits should have a daily maintenance fluid requirement between 1.75 to 2.75 Liters11, 19, 20. In a recent study, perioperative maintenance fluid was given 3 liters of water and 154 mmol of sodium and it was considered a ‘standard’ fluid regimen21 although it is well over the required daily maintenance. Some studies have use ‘restricted’ fluid regimen and have provided to the patients the appropriate fluid requirement21, 22. While others have use in true sense of restrictive fluid by giving less than the daily requirement14, 23. However, the exact amount that is prescribed may not necessary be the amount that is given. There can be a slight variation to actual practice.

Criteria for considering studies for the Systematic Review

The criteria for the inclusion for this study are based on adult population who are more than 18 years of age, who underwent elective major abdominal operation. Both open and laparoscopic abdominal surgery, exclude gynecological surgery and transplant surgery. The reviews involved looking at perioperative fluids described as ‘restrictive’, ‘liberal’ and or ‘standard’ depend on the amount of volume of fluid that is design to administer. In some studies words, like interventions, goal directed fluid and study fluid is used to denote less amount of fluid comparably to the other and therefore is carefully interpreted as restrictive.

Consideration is also given to the time in which particular fluid regime is administered and hence will define perioperative fluid. Fluid that is administered within any hospital environment on a patient a day before surgery, continue through the operation and involves 24hrs after surgery. Although one study in this analysis involves during the first 8 hours post-surgery.

The type of fluid use is considered in this study and is accepted for both colloids and crystalloids. Blood and bloods products were used by some studies within this review but were used in intention-to-treat and not included in individual study protocol. During the procedure when there is a need for blood it is overly substituted ml for ml with colloids or a higher amount of crystalloid is given depended on the protocol. Analysis of result for the study is done accordingly.

All studies of this review satisfy the criteria for inclusion if and when final outcome is assessed. Primary outcome comprises one or two endpoint and any other outcomes are measured as secondary as defined in the review.

Outcome measure

Primary outcome measures on all studies included here is on the length of hospital stay (LOS) after the surgery. Some studies prefer to use terms like surgical readiness for discharge (RfD) as a strict guideline to ascertain their objective of study. This was done in order to avoid reasons of hospital prolong stay due to social and economic reasons about the patient. One study21although was not clear on the LOS, uses complications as major and minor as its primary and secondary endpoints respectively. All of these studies use complications and death as their secondary outcome and analysis was done accordingly.

Search methods for identification of the studies

Randomized Control Trials (RCT) compare the effects (outcome) of restrictive, standard, liberal, control, or conservative fluids and either crystalloid and colloids during peri-operative period of major abdominal surgery was searched. Multi-data base system using Embase, Medline, Scopus were searched from 1992 to March 2022. Search terms including, ‘restrictive fluid’ ‘standard fluid’ ‘liberal’, peri-operative fluids, intravenous fluid, colonic resection, major abdominal surgery and or Gastro intestinal surgery. Combination of Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT were used. Individual articles were also search from Google scholar as few articles were difficult accessing from the main domain. Result from the primary search was then screened according to the inclusion criteria. Potential articles were hand –searched and related articles included in the reference or previously cited were sought. Articles appear to have been reported from laboratory work and on animals were excluded. Only English language was predominantly included for the analysis in this review.

Data collection and analysis

The progressive characteristics of the studies were further assessed for uniformity on the data. All fluids administer should define the perioperative period. Method of randomization use in allocating patients, concealment of study patient, and type of blinding individual or investigating team and any other circumstances like protocol violation during study were assessed comprehensively to determine the quality of the methods and also bias related contamination. The quality of the study was assessed using the Scottish Intercollegial Guidelines Network (SIGN).30The included studies are carefully screen for the time (pre, intra, post operative) when fluid is administered according to peri-operative course. It demonstrates the intervention of the study and accordingly assessed the outcome. The total amount of fluid administered is recorded for analysis. Other special intervention like fasting time before operation and bowel preparation, duration of operation, type of anesthesia and post operative analgesia are listed in Table 1 to enhance our review for any heterogeneity and uniformity to the studies.

Primary analysis includes all the RCT studies as identify above with measurable end point. The consistent endpoints are the length of hospital stay (LOS) or Readiness for Discharge (RfD) and complications. Therefore, the studies which identified these outcomes should constitute the secondary analysis. Two studies as mention before were not clear on their LOS, although measuring complications would ultimately lead to variation to the LOS measurement. Goal directed fluid therapy and Doppler studies were excluded.

Statistics

RevMan 5.0 software program (The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) was used for the analysis of the outcome using the standard methods recommended by the Cochrane collaboration29. Pooled analysis was performed using the random-effects model with Mantel- Haenszel method. Effect sizes for dichotomous variables was calculated and is presented as risk ratio with 95 % CI and for the continuous outcome is given as weighted mean differences (WMD). Heterogeneity of the included studies was assessed by considering the I2and Chi square (X2) P value. The threshold value for I2 are 25%, 50%, and above 50%, thereby representing low, moderate and high heterogeneity respectively.

Result

Characteristics of the studies

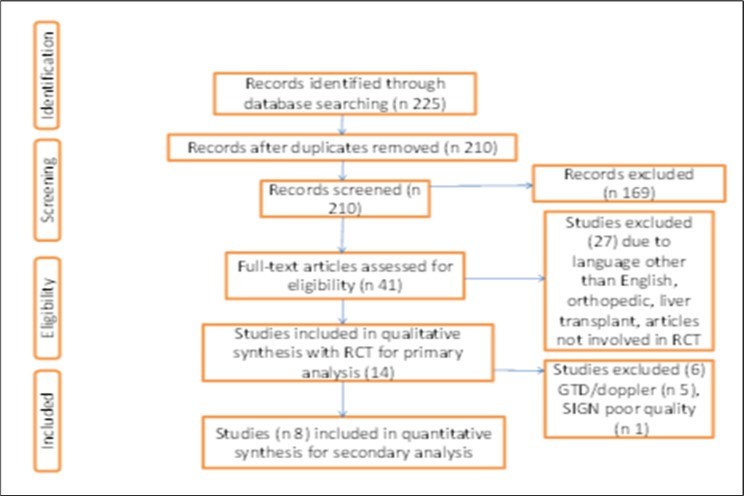

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- analysis (PRISMA) statement (Figure 1) illustrates the studies identified through our initial search. Fourteen (14) studies have defined our criteria were selected in the primary analysis. Goal directed fluid therapy (GDT) or use of Doppler to monitor the amount of fluids given was not part of this review32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40and therefore, five studies excluded. Only one was excluded as the study was not blinded and its concealment allocation was poor 31. The final eight (n 8) satisfied our search criteria and study quality according to the SIGN methodology assessment.

Figure 1.Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement summary search for and selection of studies. RCT, randomised controlled trials, SIGN- Scottish Intercollegial Guidelines Network.

There were total of 769 patients included in the final eight 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 randomized clinical trials. The characteristic of each study is summarized in Table 1. Five studies 21, 24, 25, 27, 28were double blinded and well concealed. Two studies 20, 23were single blinded and one study 26 however did not specify either patient or investigator was blinded. Randomization was done by computer generating randomization in three studies 21, 27, 28 by sealed envelope method 20, 24, 25, 26 and telephone randomization in one23. All studies were done in a single center except one.21 Most of the operation done for the study were for colorectal and only two included studies 26, 27 were done for abdominal vascular aneurysm since it was an elective laparotomy satisfying the criteria. Bowel preparation for all studies involving the left sided colorectal procedures except for two studies 21, 26. Even bowel preparation was done for the abdominal vascular surgery in one study27.

Outcome measure

Although the eight studies have assessed the outcome as either Length of hospital stay (LOS) or range of complications. When primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed, four studies 21, 24, 25, 26use complications as their primary outcome and three studies23, 27, 28 use length of hospital stay as their primary outcome. However the study by Lobo et al20 have used gastric emptying time to both solid and liquid as his primary outcome and length of hospital stay as his secondary outcome. Complication ranges from wound infection, delay organ function, organ failure and death. While, McArdle et al 23have further classify their complication in to minor and major. The major complication then becomes the primary outcome measure. In the study by Nisanevich and his colleagues, they include death as a major complication and have used to assess their primary outcome25. However, none has died from their study. Readiness for discharge (RFD) was used to denote patients who are medically fit and have been discharge by their attending surgical team but has remain in the hospital due to other social issues. Vermeulen et al 28 reported study violation due to severe complications experienced by 40 % of the patients undergoing restrictive fluid regime. Also significantly increase in the length of hospital stay in restricted group (12.3 vs 8.3 days) as compare to liberal fluid group. Three studies assessed fluid given in the post operative period only 20, 27, 28. Otherwise the rest of the studies assessed fluids administration during pre, intra and post operative period.

Table 1. Showing the characteristics of the study.| Studyl intervention/ year | Operation | Group study! | No. of | Age(yrs) | Preoperation Fastin | Intraoperative | Fluid regime, type (mls) |

| author terminology | patient | Median IQR | Time /Bowel prep | monitoring | crystalloid/ colloid | ||

| Brandstrup/ Intra Op/ | Colorectal | Hestrictive | 69 | 64(42-90) | Clear fluid, 2hrs before | GA/Epidurall non- | No preload, no third space replacement |

| post surgeryl Blind 2003 | surgery | invasive inotropes | 500mls/5% Glucose, 500ml, HAES 6% N/S | ||||

| Standard | 72 | 69(41-88) | ASA 1-3, No bowel prep | 7mlsihr, 5ml/2nd ht. 3mls rest of hr. R Blood replace | |||

| HAES 6%7ml. S, 1-1.5L NS/500 ml of loss, PO cont | |||||||

| Mackay et all Intra Op | Colorectal | R <2L water, 77mmol Na | 39 | 73.2(65.3-78.0) | Free fluid, high calorie | GA/PCA, Oral | |

| Day 1PO/ Blind 2006 | 124hr | 4hrs before surgery | Standard protocol | R 4.5(4.0-5.62)L 229(131-332) mmol, '4 days PO | |||

| 3L water, 154mmol Na | 41 | 72.6(65.3-82.9) | No bowel prep. except | ||||

| 124hr | L hemi-colectomy | 8.75(8.0-9 8)L, 560(477-667)mmol | |||||

| Lobo et all Post Op/ 2002 | Colorectal | HK 2Lwater/ " mmol | 10 | 62.3(52.5-67.2) | free fluid 4hrs before | PCA/ morphined | H 0.5L 0.9% saline, 15L 5% destrose or 2L |

| Nal24hr | Surgery | no epidural | 4.3% desirose | ||||

| S>3L water/ 154mmol | 10 | 59(55.3-66.7) | Bowel prep. L hemicolect | S 1L0.9% saline & 2L5% destrose | |||

| Na/24hr | tomy, 2 Sachet of Picolax | ||||||

| Gonazalez et all Post Op/ | Abdominal | R 1500mls/24hrs | 20 | 65.5(62.1-69) | All patients got bowel | GA/Epidural | R 1500mls (0.9% Saline) plus 40mmol K+/day |

| Observer Blinded (Anesth | Vascular | prep. Phosphate enema | Standard protocol | ||||

| etist & Inv. team Blinded/2009 | 2500mls/24hrs | 20 | 62(56.7-67.2) | Fast 12hrs prior | ASA 1-3 | 1.5L(0.9% saline plus 1.0L (5% destrose) | |

| 40mmol K+/day | |||||||

| McArdle et all Ublinded/ | AAA repair | Restrictive | 10 | 74(58-80) | All patients lasted from | GA/ Epidural | R No preload, 4mls/kg/hr HS 83ml/hr HS on PO, |

| Intra & Post Op 2005 | 12 midnight | 1.9% saline * 1.5L 5% Day 1-5 | |||||

| Standard | 11 | 75(64-86) | same | S Preload 10mlsikg 0. 9% saline IO 12mlikg/hr HS | |||

| PO 1HS. 1L 0.9% saline +2L | |||||||

| Kabon et all Intra & Post | Colonic | R small volume | 124 | Mean 535014 | Fasted Bhrs, all patients | GA | RIO 8-10ml/kg/hr RL & PO, D1PO: 2mlsikg/hr |

| Operation 2005 | Resection | have bowel prep | |||||

| $ Large Volume | 129 | Mean 62 | same | S Preload: 10ml/kg RL, IO 16-18ml/Kg/Hr then | |||

| PO 2mlsikg/hr until day 1. | |||||||

| Nisanevich et all Intra Op | Major Abdo- | Restrictive | 77 | Mean 635013 | All patients have bowel | GA/Epidural | R ID: 4ml/kg/hr RL, 250mls bolus, if BP. urine output |

| Double Blind 2005 | men surgery | prep. tasted from 12 MN | |||||

| Standard | 75 | Mean 595012 | same | S. Initial bolus 10ml/kg/hr RL, IO: 12ml/Kg/Hr, & | |||

| 250mls bolus FLBP, UO | |||||||

| Vermuelen et all Post Op | Gastric/Bowel | Restrictive 15L/24hr | 30 | Mean 55 SD 15 | NR | GA Epidural | R. 1.0L 0.9% NaCl & 500mls 5% glucose. |

| Extend Blinded 2009 | Rectum/Bile/ | ||||||

| Pancreas Exclude | Standard 2. 5L/24hrs | 32 | Mean 545015 | Bowelprep x2 enema | S. 15L 9% NaCl& 1.0L of 5% glucose | ||

| Liver, esophagus |

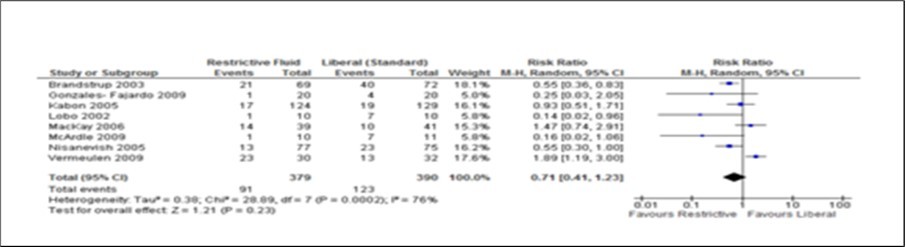

Figure 2.Forest plot of comparison: complication between Restrictive and Liberal IV Fluids groups. Primary analysis using eight studies. M-H, Mantal- Haenszel.

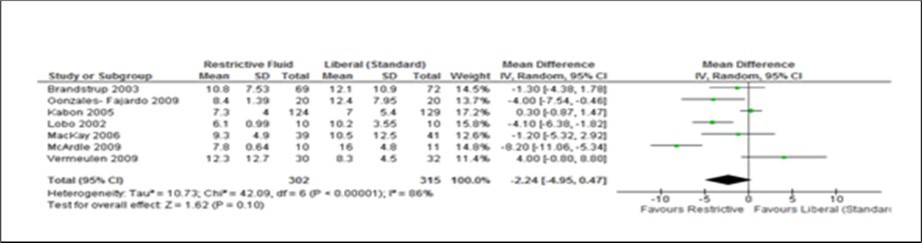

Figure 3.Forest plot of comparison: Length of hospital stay (LOS) for Restrictive and Liberal (standard) groups. Primary analysis includes seven studies only. Data for one study 25 were mentioned as median (range) and therefore could not be included in to the forest plot. IV, inverse variance.

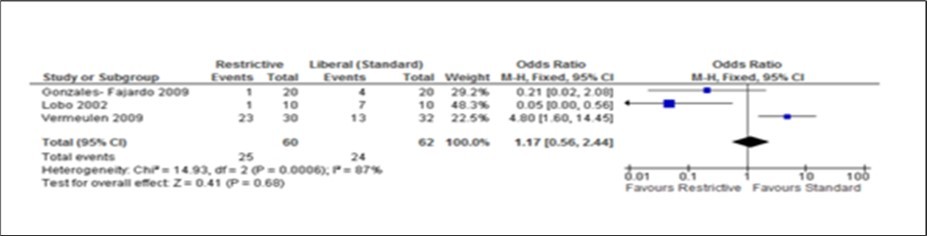

Figure 4.Forest plot of comparison: complication during post abdominal surgery using Restrictive and Liberal (standard) IV Fluids. Only three (3) studies assessed the fluids use during the post surgery period.

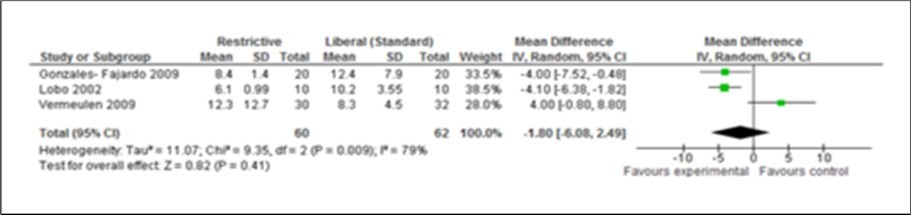

Figure 5.Forest plot of comparison: Length of hospital stay (LOS) during post operation using experiment (Restrictive) and control (Liberal) IV fluid

Discussion

This meta-analysis have pooled data for restrictive versus liberal or standard fluids use for peri-operative abdominal surgical patients. It has shown from the forest plot that both complication and length of hospital stay has shown to be favorable amongst restrictive fluid group. However, it cannot be firmly established that this is true. There are obvious differences in the study design and methodology used to assess the study. High test for heterogeneity have also suggested for further standardization in the overall design and methodology.

The two measurable outcomes in this analysis were the common endpoints used for all studies in this meta-analysis. Assessing these variables as either primary or secondary was not consistent and uniform in the eight studies. However, restrictive fluids tend tohave better outcome with less complications and shorter hospital stay. A reduction of 2 days (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5) seen in the restrictive study group then the liberal group. The use of either liberal or restrictive fluid in the post operative study have shown no effects on the outcome. It is unfortunate that this evidence is seen in three studies only. Therefore, a firm conclusion from this result cannot be established.

Balanced saline is normally used to replace intercellular deficit of electrolyte and water. Unbalanced saline (0.9% Saline) is mostly reserve for the gastric loses through vomiting or naso- gastric drainage. It is known that excessive salt and water causes hyperchloremia acidosis which affects the renal blood flow and glomerula filtration rate 41, 42. In a study by Drummer et al43 with infusion of saline amongst healthy volunteers have shown that it takes over 2 days to excrete an infusion of 2 litres of 0.9% saline in 25 minutes. It is due partly to the slow and sustained suppression of rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and also the hyperchloremia acidosis causing poor renal perfusion. Most of the retained fluid is station within the interstitial compartment and therefore, causing edema 44, 45, 46. Splanchnic edema can result in increased intra-abdominal pressure, abdominal compartment 47 pressure and further reduces mesenteric blood flow with decrease gut perfusion and gut functional failure and may cause dehiscence to anastomosis48. Hyperchloremia acidosis also causes reduce gastric blood flow and decrease gastric intramucosal pH in elderly patients49. Also, excess saline causes hyper polarization of neurotransmitter and impairment of mitochondria activity at the cellular level50.

It is important to note that individual patients with different surgical pathology process demand judicious use of fluid. Especially in abdominal surgery, the aim is to provide ideal fluid use with resulting zero fluid balance and less or no weight gain. Equally important is to note that excessive fluid restrictive can result in decrease venous return and poor cardiac output. Subsequently reduce tissue perfusion and hence oxygen delivery with hypoxia at the wound ultimately resulted in poor wound healing and infections. Also increase in the viscosity of pulmonary mucus resulting in mucus plug formation and ateletactasis51. Balance fluid volume of 1.5L to 2.5Liters per day of maintenance fluid as proposed by Lobo et al9 have shown significant improvement in both length of hospital stay and less complications in their meta-analysis. Similarly, patients with ongoing loses from fistulae, stoma or other gastro intestinal loses needs to be replaced with appropriate fluids and electrolytes while maintaining their daily requirements.

The limitation to this meta-analysis is on study methodology. Literature pertaining to restrictive and liberal fluids use during peri-operation on surgical patients with major abdominal surgery are inconsistent regarding their definition, methodology and outcome measurements. Therefore, it cannot be certain that a uniform volume of fluid can be applied to every abdominal operation. In future there is need for more multi center randomized studies on fluids for specific surgical procedure by using both fixed volume regimen and goal directed concept52. The approach is to combine both strategies because they replace extra vascular and intravascular compartment respectively.

Conclusion

Within the context of this study, appropriate fluid volume and electrolyte should be given to the patient to ensure good cardiac output and tissue perfusion and to make sure that patient has a zero fluid balance and less weight gain. However, the ideal fluid regime can be in the narrow range and therefore can easily cause fluid related complications which can be detrimental to the overall patient recovery.

Acknowledgment

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.O’ Shaughnessy WB.Proposal of a new method of treating the blue epidemic cholera by the injection of highly oxygenized salts in to the venous system. , Lancet 1831, 366-371.

- 2.Latta T.Malignant cholera: Documents communicated by the central Board of health, London, relative to the treatment of cholera by the copious injection of aqueous and saline fluids into the veins. , Lancet 1832, 274-280.

- 4.Ringer S.A further contribution regarding the influence of the difference constituent of the blood on the contraction of the heart. , J Physiol 4, 29-42.

- 5.Ringer S.A third contribution regarding the influence of the inorganic constituents of the blood on the ventricular contraction. , J Physiol 4, 222-225.

- 7.Matas R. (1924) The continued intravenous “drip”: with remarks on the value of continued gastric drainage and irrigation by nasal intubation with a gastroduodenal tube (Jutte) in surgical practice. Ann Surg. 79, 643-661.

- 8.Nussmeier N A, Searles B E. (2009) The next generation of colloids: ready for “prime time”? AnesthAnalg. 1715-1717.

- 9.Krishna K Varadhan, Dileep N Lobo. (2010) Symposium 3: Death by drowning, a meta – analysis of randomized controlled trials of intravenous fluid therapy in major elective open abdominal surgery: getting the balance right. Proceedings of the Nutition Society 69, 488-498.

- 10.Powell-Tuck J, Gosling P, Lobo D N. (2008) British consensus guidelines on intravenous fluid therapy for adult surgical patients. FIFTASUP. Available fromhttp://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/bapen_pubs/giftasup.pdf (accessed 12th.

- 11.Lobo D N. (2004) Sir David Cuthbertson medal lecture. Fluid, electrolytes and nutrition: physiological and clinical aspects. , ProcNutrSoc 63, 453-466.

- 13.Vermuelen H, Hofland J, Legemate D A. (2009) Intravenous fluid restriction after major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded clinical trial. Trials10, 50

- 14.Mark P Yeager, Brian C Spence. (2006) Perioperative Fluid Management: current consensus and controversies. , Seminars in Dialysis 19, 472-479.

- 15.Lobo D N, Macafee D A, Allison S P. (2006) How perioperative fluid balance influence post operative outcomes. Best Pract Res ClinAnaesthesiol20. 439-455.

- 16.Lobo D N. (2009) Fluid overload and surgical outcome: another piece in the jigsaw. Ann Surg249. 186-188.

- 18.DAB Turner. (1996) Fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance. In Textbook of Anaesthesia [AR Aitkenhead and G Smith, editors] , New York: Churchill Livingstone 361-375.

- 19. (2005) Fluid, electrolyte and nutrition replacement. In The New Aird’s Companion in Surgical studies Lobo DN & Allison SP , London: Churchill Livingstone 20-41.

- 20.Lobo D N, Bostock K A, Neal K R. (2002) Effect of salt and water balance on recovery of gastrointestinal function after elective colonic resection: a randomized controlled trial. , Lancet 359, 1812-1818.

- 21.Brandstrup B, Tonnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R. (2003) Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on post operative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens: a randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg238. 641-648.

- 22.Holte K, Foss N B, Andersen J. (2007) Liberal or restrictive fluid administration in fast-track colonic surgery: a randomized, double blinded study. , Br J Anaesth99 500-508.

- 23.MacKay G, Fearon K, McConnachie A. (2006) Randomized clinical trial of the effect of post-operative intravenous fluid restriction on recovery after elective colorectal surgery. , Br J Surg93 1469-1474.

- 24.Kabon B, Akca O, Taguchi A. (2005) Supplemental intravenous crystalloid administration does not reduce the risk of surgical wound infection. AnesthAnalg101 1546-1553.

- 25.Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G. (2005) Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intraabdominal surgery. Anesthesiology103 25-32.

- 26.McArdle G T, McAuley D F, McKinley A. (2009) Preliminary results of a prospective randomized trial of restrictive versus standard fluid regime in elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Surg250. 28-34.

- 27.Gonzalez-Fajardo J A, Mengibar L, Brizuela J A. (2009) Effects of post-operative restrictive fluid therapy in the recovery of patients with abdominal vascular surgery. , Eur J VascEndovascSurg37 538-543.

- 28.Vermeulen H, Hofland J, Legemate D A. (2009) Intravenous fluid restriction after major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded clinical trial. , Trials 10, 50.

- 29.JPT Higgins, Green S. (2010) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated.

- 30. (2012) Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Improvement Scotland. (Last modified 27th/ 02/12). Available from http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/checklist2.html (accessed on 13th .

- 31.Brian H Cuthbertson, Marion K Campbell, Stephen A Stott, Elders Andrew. (2011) A pragmatic multi-center randomized controlled trial of fluid loading in high- risk surgical patients undergoing major elective surgery – the FOCCUS study. Critical Care.

- 32.Pearse Rupert, Dawson Deborah, Fawcett Jayne. (2005) Early goal-directed therapy after major surgery reduces complications and duration of hospital stay. A randomized, controlled trial. Critical Care,9:R687-693

- 33.Challand C, Struthers R, J R Sneyd, P D Erasmus. (2011) Randomized controlled trial of intra-operative goal-directed fluid therapy in aerobically fit and unfit patients having major colorectal surgery. , British Journal of Anaesthesia108: 53-62.

- 34.Futier Emmanuel, Antoine Petit Jean-MichealConstantin. (2010) Conservative vs Restrictive individualized goal directed fluid replacement strategy in major abdominal surgery. Arch Surg;145:. 1193-1200.

- 35.S M Abbas, A G Hill. (2008) Systematic review of the literature for the use of Oesophageal Doppler monitor for fluid replacement in major abdominal surgery. , Anaesthesia 63, 44-51.

- 36.S E Noblett, C P Snowden, B K Shenton, A F Horgan. (2006) Randomized clinical trial assessing the effect of Doppler-optimized fluid management on outcome after elective colorectal resection. , British Journal of Surgery 93, 1069-1076.

- 37.D H Conway, Mayall R, M S Abdul-Latif, Gilligan S, Tackaberry C. (2002) Randomised controlled trial investigating the influence of intravenous fluid titration using oesophageal Doppler monitoring during bowel surgery. , Anaesthesia 57, 845-849.

- 38.Gatt M, Anderson A D G, B S Reddy, P Hayward- Sampson, I C Tring et al. (2005) Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major colonic resection. , British Journal of Surgery 92, 1354-1362.

- 39.Srinivasa S, Taylor M H G, Sammour T, A, G A. (2011) Oesophageal Doppler-guided fluid administration in colorectal surgery: critical appraisal of published clinical trials. ActaAnaesthesiolScand,55: 4-13.

- 40.Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Holte K, Secher H, Kehlet H. (2007) Monitoring of peri-operative fluid administration by individualized goal-directed therapy. , ActaAnaesthesiolScand 51, 331-340.

- 42.Hansen P B, O Jensen BL &Skott. (1998) Chloride regulates afferent arteriolar contraction in response to depolarization. Hypertension32,1066- 1070.

- 43.Drummer C, Gerzer R, Heer M. (1992) Effects of an acute infusion on fluid and electrolyte metabolism in humans. , Am J Physiol262 744.

- 44.Lobo D N, Stanga Z, JAD Simpson. (2001) Dilution and redistribution effects of rapid 2 liters infusion of 0.9% saline and 5% dextrose on haematological parameters and serum biochemistry in normal subjects: a double blind cross over study. ClinSci (Lond)101. 173-179.

- 45.Lobo D N, Stanga Z, Aloysius M M. (2010) Effects of volume loading with 1 liter intravenous infusions of 0.9 % saline, 4% succinylated gelatin (Gelofusine) and 6% hydroxyethyl starch on blood volume and endocrine responses: a randomized three way cross over study in healthy volunteers. Crit Care. Med38 464-470.

- 46.Reid F, Lobo D N, Williams R N. (2003) (Ab)normal saline and physiological Hartmann’s solution: a trandomized double blinded cross over study. ClinSci (Lond)104. 17-24.

- 47.Balogh Z, McKinley B A, Cocanour C S. (2003) Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg138. 637-642.

- 48.Lobo D N. (2004) Sir David Cuthbertson medal lecture. Fluid, electrolytes and nutrition: physiological and clinical aspects. ProcNutrSoc63 453-466.

- 49.Wilkes N J, Woolf R, Mutch M. (2001) the effects of balanced versus saline- based hetastarch and crystalloid solution on acid- base and electrolyte statues and gastric mucosal perfusion in elderly surgical patients. , AnesthAnalg93 811, 816.

- 50.Cotton B A, Guy J S, Morris JA Jr. (2006) The cellular, metabolic, and systemic consequences of aggressive fluid resuscitation strategies. , Shock 26, 115-121.

- 51.Lobo D N, Allison S P. (2005) Fluid, electrolyte and nutrition replacement. In the New Airds Companion in surgical studies [KG Burnand, AE Young, J Lucas et al. editors] , London: Churchill Livingstone 20-41.

- 52.Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Holte K, Secher H, Kehlet H. (2009) Liberal vs. restrictive peri-operative fluid therapy –a critical assessment of the evidence. , ActaAnaestheiolScand53,: 843-851.

- 54.Hwang G, Marota. (1997) JA,: Anesthesia for abdominal surgery,Clinical Anesthesia Procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Edited by. 330-46.

- 55.Sendak M. (1993) Monitoring and management of perioperative fluid and electrolyte therapy, Principles and Practise of Anesthesiology, 1st edition. Edited by. , New York, Mosby- Year Book 863-966.

- 56.Tonnessen A S. (1990) Crystalloids and colloids, Anesthesia, 3rd edition. Edited by Miller RD. , New York, Churchill Livingstone 1439-65.

- 57.Jenkins M T, Giesicke A H, Johnson. (1975) ER: The postoperative patient and his fluid and ellevctrolyte requirements. , Br J Anaesth; 47, 143-50.